Introduction

Depending on the effect on the electrons of the atoms they hit, the radiation can be classified into exciting and ionizing, in particular according to the parameter of the energy they carry: a radiation with E less than 10 eV will have exciting effects, with E greater than 10 eV instead ionizing.

Ionizing radiation

Ionizing radiations as said are such only if E > 10 eV, i.e. only if they are carriers of a high energy packet, especially characteristic of corpuscular radiations: in fact, the higher the mass, the more energy is conveyed and the greater the probability of impact. In fact, radiation with large particles will disperse this great energy in a few impacts, potentially generating greater damage than smaller, less energetic particles, but which give up their energy in a more homogeneous way.

This transfer induces damage to our organism both directly and indirectly:

Direct damage (predominant if the radiation has high LET, i.e. with high ionization density of the radiation) means the interaction between radiation and biological macromolecule, in particular DNA, the most radiosensitive biological macromolecule.

The interaction between DNA and ionizing radiation is resolved in a real rupture of the biological molecule of variable entity depending on the amount of energy transferred, which leads to an error in the correct and physiological DNA sequence; in the worst cases it can sometimes even break the double filament if not the entire chromosome, but always on condition that they are able to impact it, data that between the radiation and the genome are intercalated numerous impediments such as lipidic membranes, organelles and cytoplasm, and (depending on the position) greater or lesser cellular and tissue layers.Always with an alteration of the DNA the indirect damage is also solved (predominant if the radiation has low LET): this happens in most cases, because statistically speaking the radiation will generally not affect a biological molecule, but the most represented molecule in our body: H2O.

This induces a homolytic cleavage with consequent formation of oxygen radicals, which are extremely reactive and therefore toxic for biological macromolecules, in particular for DNA, which will therefore undergo their reactions, altering itself.

As can be seen, both direct and indirect effects of ionizing radiation lead to alterations in DNA and therefore increase the physiological probability of tumorigenesis.

But DNA alterations are only one of a wide range of possible irradiation consequences.

In fact, based on the dose of radiation absorbed in a hypothetical pan-irradiation, we can distinguish various clinical (evil by rays) and subclinical profiles, depending on the radiosensitivity of different tissues and therefore organs and systems.

As far as subclinical profiles are concerned, there is a dose, corresponding to the interval 0 Gy < x< 0.5 Gy, which does not entail any visible clinical consequence in the short term, since this quantity is sufficient to damage only and only the most radiosensitive cell types, the stem ones, due to their proliferative peculiarity, thus predisposing to neoplasms (which often have a subclinical course for two thirds).

The damage that these irradiated stem cells suffer clearly originates from the damage to their genome, which can lead to multiple pathological outcomes such as cell death, teratogenesis and carcinogenesis.

However, damage can also occur in regions of DNA that are not expressed or in any case not used by the cell type that suffers it, being therefore classified as silent mutations, as they have no phenotypic effect.

Exciting radiation

Among the leading exponents of this category of radiation we find the infrared rays and herzian waves: both types are able to penetrate deep into the body by heating the internal organs, thus causing hyperthermia but without burns or damage of any kind.

Also the UV rays can be counted among the exciting radiations, but only those present inside the ozonosphere. In fact, ultraviolet radiation can be divided into three types: UVA, UVB and UVC. The wavelength of UV is therefore wide, ranging from near X-rays (UVC) to visible light (UVA and UVB).

UVA and UVB have low E, so they are classified as exciting radiation, while UVC are to all intents and purposes ionizing radiation, so much so that they can fragment DNA. However, 99% of UVC is blocked by the ozonosphere, thus becoming a completely irrelevant portion of the sun's rays that reach us, consisting mainly of UVA, the least harmful, and UVB, which are the right compromise between size and energy to reach the DNA and alter it. UVA rays, on the other hand, having a slightly smaller size, only 1% of the cases are able to reach the subcutaneous layer, but due to their smaller size and therefore less energy, they are less harmful than UVB rays.

So ultraviolet radiation brings with it a combination of benefits and evils: on the one hand we need to expose ourselves to these rays to produce, precisely at the level of the epidermis, the fundamental vitamin D from its biologically inactive precursor. On the other hand, however, we have the risk of different levels of burns up to pan-irradiation with hypovolemic shock, but not only.

Although UVA and UVB are exciting radiations, and therefore do not have enough energy to damage even the most sensitive macromolecule or DNA, there are more sensitive portions within DNA than others, namely the dimeres T-T (sequences of two consecutive thymines), which are inherently unstable and can be affected by such radiation. In fact, if we hit adenine, guanine, cytosine with such exciting radiation we do not obtain consequences, but the thymine instead enters a transitory state of greater energy so that if it is contiguous to another equally excited thymine it tends to form a covalent bond with it that induces the two thymines to lose the bond with the corresponding adenines on the contralateral helix, generating between them a covalent bond able to distort the double helix of DNA.

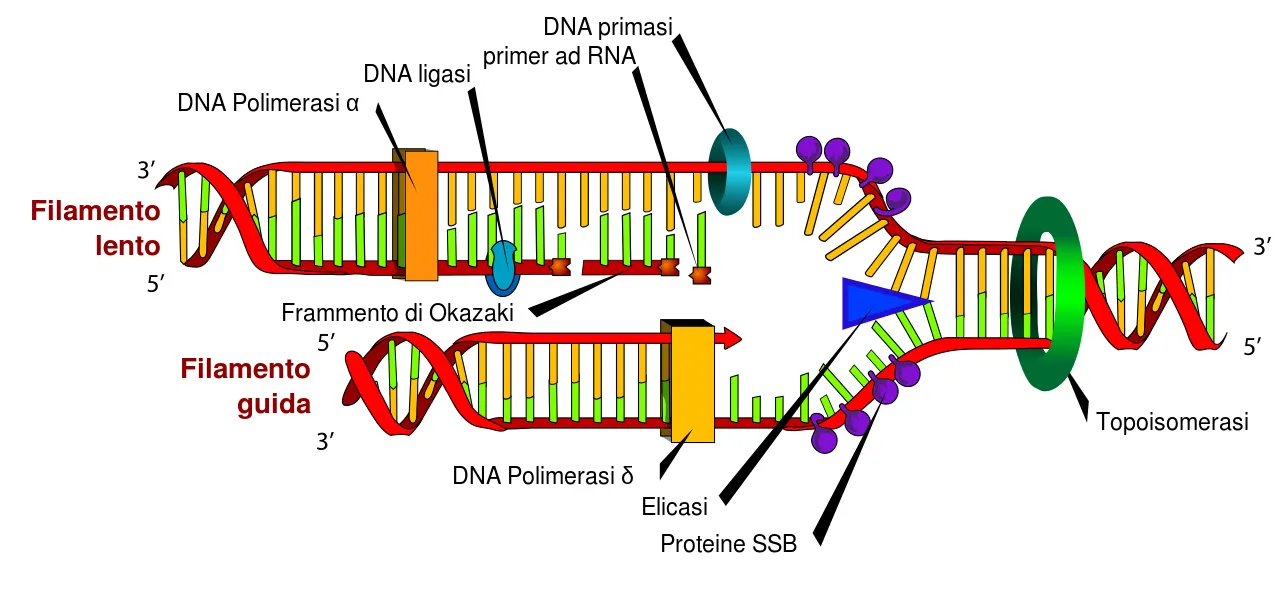

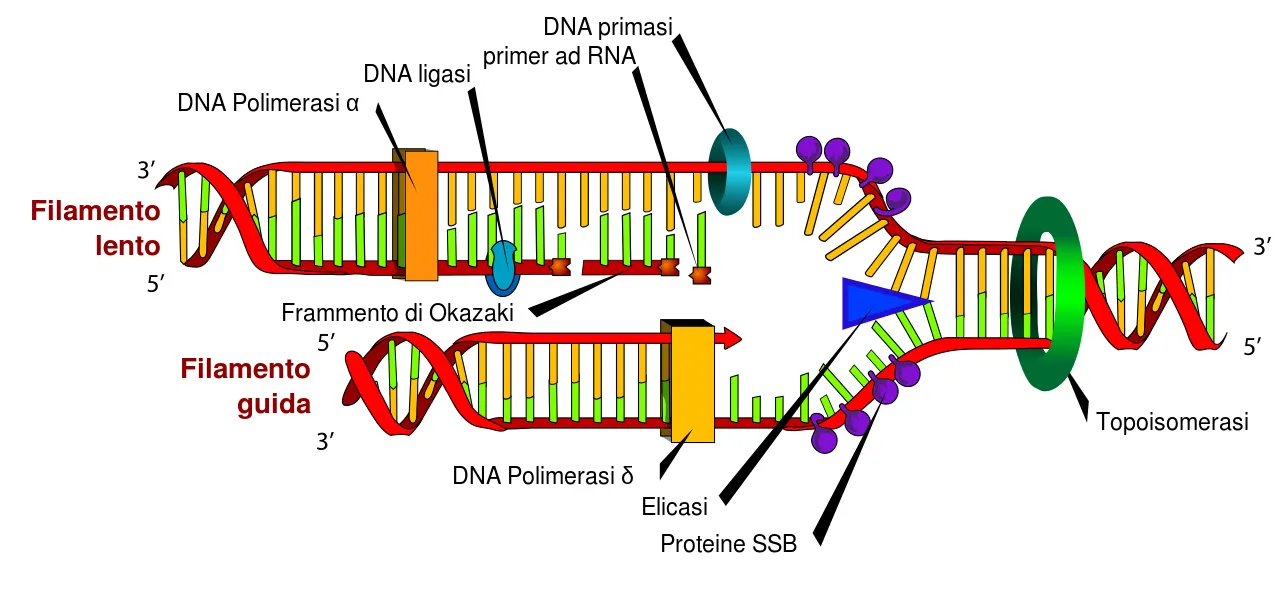

If this error is not repaired before the S phase, it will be the DNA polymerase that will have to face the problem, but often in front of such dimeres it makes a mistake, inserting one or both bases different from the physiological structure, thus causing an error that, although limited, still remains a mutation, which like any other mutation can have none or multiple phenotypic effects depending on where it occurs. However, it has been demonstrated that these thymine dimers are particularly represented at the level of the hexonic sequences of the main cellular oncosuppressant: the gene p53, which, given the multiple anti-oncogenic activities it performs, it is not surprising that its erroneous functioning can expose to a high risk of accumulating numerous gene errors that, taken as a whole, can lead to neoplastic genesis.

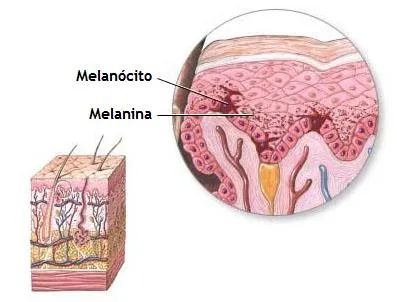

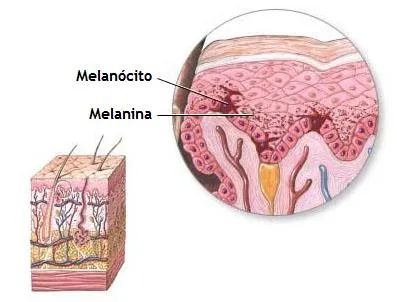

Considering the damage to T-T dimers related to cells extending from the keratinized layer of the epidermis to the basal layer, it may have an oncogenic effect on the cells most sensitive to radiation, i.e. those in active proliferation such as the cells of the basal layer (the stem cells of keratinocytes) and melanocytes; in fact, frequent are the basal-cellular carcinomas and skin melanomas** associated with exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

Precisely to resist this environmental stress our body has evolved in such a way as to have melanocytes: they produce (and yield to the epithelial cells) melanine, whose task is to shield everything below the epidermis from such UV insults but not only, as the epidermis itself uses melanin for the same reason, accumulating it and placing it above the area most in need of such radiation protection, i.e. the nucleus. This is how the protective action of tanning is expressed.

The DNA repair systems that are able to recognize and repair a mutation using the unaltered DNA helix as a mold are varied, but the one most directly involved in repairing UV damage is the excision repair system, the Nucleotide excision repair (NER).

However, if this mechanism is defective somewhere, we have the clinical picture of the Xeroderma Pigmentose, a genetic disease characterized by the lack of one or more genes coding for DNA repair enzymes by excision. The affected individual will therefore be extremely more susceptible to the development of skin melanomas and basal cell carcinomas since the damage induced by even minimal sun exposure cannot be repaired, accumulating up to tumorigenesis. Being a genetic disease, it already affects children and prevents a normal course of daily life: the individual must be constantly protected by special and cumbersome protections to avoid that within a few years a terrible range of skin cancers start to arise.

Pictures

Sources

Introduzione

In base all’effetto che hanno sugli elettroni degli atomi che colpiscono, le radiazioni possono essere classificate in eccitanti e ionizzanti, in particolare secondo il parametro dell'energia di cui sono portatrici: una radiazione con E inferiore a 10 eV avrà effetti eccitanti, con E superiore a 10 eV invece ionizzanti.

Radiazioni ionizzanti:

Le radiazioni ionizzanti come detto sono tali solo se E > 10 eV, ossia solo se sono portatrici di un elevato pacchetto energetico, caratteristico soprattutto delle radiazioni corpuscolari: infatti maggiore è la massa, maggiori sono l’energia convogliata e la probabilità di impattare. Infatti le radiazioni con grosse particelle disperderanno tale grande energia in pochi impatti, generando potenzialmente danni maggiori di particelle più piccole, meno energetiche, ma che cedono la loro energia in maniera più omogenea.

Tale cessione induce danni al nostro organismo sia in modo diretto che indiretto:

Per danno diretto (predominante se la radiazione ha elevato LET, ovvero con elevata densità di ionizzazione della radiazione) si intende l’interazione tra radiazione e macromolecola biologica, in particolare DNA, la macromolecola biologica maggiormente radiosensibile.

L’interazione tra DNA e radiazione ionizzante si risolve in una vera e propria rottura della molecola biologica di entità variabile in base alla quantità di energia trasferita, che porta ad un errore nella corretta e fisiologica sequenza di DNA; nei casi peggiori si può arrivare talvolta anche a spezzare di netto il doppio filamento se non l’intero cromosoma, ma sempre a patto che riescano ad impattarvi, dati che tra la radiazione e il genoma sono intercalati numerosi impedimenti quali le membrane lipidiche, organuli e citoplasma, e (in base alla posizione) maggiori o minori strati cellulari e tissutali.Sempre con un’alterazione del DNA si risolve pure il danno indiretto (predominante se la radiazione ha basso LET): ciò avviene nella maggioranza dei casi, in quanto statisticamente parlando la radiazione generalmente non colpirà una molecola biologica, bensì la molecola più rappresentata nel nostro organismo: H2O.

Ciò ne induce una scissione omolitica con conseguente formazione di radicali dell’ossigeno, estremamente reattivi e dunque tossici per le macromolecole biologiche, in particolare per il DNA, il quale dunque si troverà a subire le loro reazioni, alterandosi.

Come si può ben vedere entrambi gli effetti, diretti e indiretti, della radiazione ionizzante portano ad alterazioni nel DNA e dunque aumentano le fisiologiche probabilità di tumorigenesi.

Ma le alterazioni al DNA sono solo una della vasta gamma di conseguenze da irradiazione possibili.

Infatti, in base alla dose di radiazioni assorbite in una ipotetica pan-irradiazione, possiamo distinguere vari profili clinici (male da raggi) e subclinici, dipendentemente dalla radiosensibilità dei diversi tessuti e quindi organi apparati e sistemi.

Per quanto riguarda i profili subclinici esiste una dose, corrispondente all’intervallo 0 Gy < x< 0.5 Gy, che non comporta alcuna conseguenza clinica visibile a breve termine, poiché tale quantità è sufficiente a ledere solo e soltanto i tipi cellulari più radiosensibili, quelli staminali, a causa della loro peculiarità proliferativa predisponendo quindi a neoplasie (che spesso hanno un decorso per due terzi subclinico).

Il danno che tali cellule staminali irradiate subiscono origina chiaramente dal danno sul loro genoma, che può condurre a molteplici esiti patologici quali, morte cellulare, teratogenesi e carcinogenesi.

Un danno può però avvenire anche in regioni di DNA non espresse o comunque non utilizzate dal tipo cellulare che lo subisce, venendo quindi classificate come mutazioni silenti, in quanto prive di effetto fenotipico.

Radiazioni eccitanti

Tra gli esponenti di spicco di tale categoria di radiazioni troviamo i raggi infrarossi e le onde herziane: entrambe le tipologie sono capaci di penetrare in profondità riscaldando gli organi interni, causando dunque ipertermia ma senza ustioni né danni di qualsivoglia genere.

Anche i raggi UV possono essere annoverati tra le radiazioni eccitanti, ma solo quelli presenti all’interno dell’ozonosfera. Infatti le radiazioni ultraviolette si distinguono in tre tipologie: UVA, UVB e UVC. La lunghezza d’onda degli UV è dunque ampia, andando da lunghezze prossime ai raggi X (UVC) fino a quelle della luce visibile (UVA e UVB).

UVA e UVB hanno bassa E, quindi sono classificate come radiazioni eccitanti, mentre gli UVC sono a tutti gli effetti radiazioni ionizzanti, tanto da riuscire a frammentare il DNA. Il 99% degli UVC però viene bloccato dall’ozonosfera, diventando quindi una porzione del tutto irrilevante dei raggi solari che giungono sino a noi, costituiti prevalentemente da UVA, i meno dannosi, e UVB, che costituiscono il giusto compromesso tra dimensione ed energia per giungere al DNA ed alterarlo. I raggi UVA invece avendo dimensione leggermente inferiore solo 1% dei casi riescono a raggiungere il sottocute, ma proprio per le loro minori dimensioni e dunque minore energia, risultano meno dannosi degli UVB.

Dunque le radiazioni ultraviolette portano con sé un connubio di benefici e malefici: da un lato abbiamo la necessità di esporci a tali raggi per produrre, proprio a livello dell’epidermide, la fondamentale vitamina D dal suo precursore biologicamente inattivo. D’altro canto però abbiamo il rischio di diversi livelli di ustioni fino alla pan-irradiazione con shock ipovolemico, ma non solo.

Nonostante UVA e UVB siano radiazioni eccitanti, e quindi non abbiano sufficiente energia per danneggiare nemmeno la macromolecola più sensibile ovvero il DNA, all’interno del DNA esistono porzioni più sensibili di altre, ossia i dimeri T-T (sequenze di due timine consecutive), che sono intrinsecamente instabili che possono essere colpite da tali radiazioni. Infatti se colpiamo adenina, guanina, citosina con tale radiazione eccitante non otteniamo conseguenze, ma la timina invece entra in uno stato transitorio di maggiore energia per cui se è contigua ad un’altra timina ugualmente eccitata tende a formare con essa un legame covalente che induce le due timine a perdere il legame con le adenine corrispondenti sull’elica controlaterale, generando tra loro un legame covalente in grado di distorcere la doppia elica di DNA.

Se tale errore non viene riparato prima della fase S, sarà la DNA polimerasi a dover affrontare il problema, ma spesso di fronte a tali dimeri sbaglia, inserendo una oppure entrambe le basi diverse dall’assetto fisiologico provocando dunque un errore che, per quanto limitato, resta pur sempre una mutazione, che come ogni altra mutazione può avere nessuno o molteplici effetti fenotipici in base a dove si verifica. Però è stato dimostrato che tali dimeri di timina sono particolarmente rappresentati a livello delle sequenze esoniche del principale oncosoppressore cellulare: il gene p53, che viste le molteplici attività anti-oncogeniche che svolge, non stupisce che un suo erroneo funzionamento possa esporre a un elevato rischio di accumulare numerosi errori genici che nell’insieme possono portare alla genesi neoplastica.

Considerando il danno ai dimeri T-T relativo alle cellule che si estendono dallo strato cheratinizzato dell’epidermide fino allo strato basale, esso potrà avere un risvolto oncogenico sulle cellule più sensibili alla radiazione, ovvero quelle in attiva proliferazione come le cellule dello strato basale (le staminali dei cheratinociti) e i melanociti; frequenti infatti sono i carcinomi baso-cellulari e i melanomi cutanei associati ad esposizione alla radiazione ultravioletta.

Proprio per resistere a tale stress ambientale il nostro organismo si è evoluto in maniera tale da disporre di melanociti: essi producono (e cedono alle cellule epiteliali) melanina, il cui compito è quello di schermare tutto ciò che si trova al di sotto dell’epidermide da tali insulti UV ma non solo, in quanto anche l’epidermide stessa usa la melanina per la medesima ragione, accumulandola e disponendola al di sopra della zona più bisognosa di tale radio-protezione, ovvero il nucleo. Si esplica in questo modo l’azione protettiva dell’abbronzatura.

I sistemi di riparazione del DNA che sono in grado di riconoscere e riparare una mutazione utilizzando come stampo l’elica di DNA inalterata sono svariati, ma quello più direttamente coinvolto nella riparazione dei danni da UV è il sistema per excisione, il Nucleotide excision repair (NER).

Se tale meccanismo però è difettoso in qualche sua parte, abbiamo il quadro clinico dello Xeroderma Pigmentoso, una malattia genetica caratterizzata dalla mancanza di uno o più dei geni che codificano per gli enzimi di riparazione del DNA per excisione. L’individuo colpito sarà dunque estremamente più suscettibile allo sviluppo di melanomi cutanei e carcinomi baso-cellulari poiché i danni indotti anche da una minima esposizione solare non possono essere riparati, accumulandosi fino alla tumorigenesi. Essendo una malattia genetica colpisce già in età pediatrica impedendo un normale svolgersi della vita quotidiana: l’individuo deve infatti essere costantemente protetto tramite speciali e ingombranti protezioni per evitare che entro pochi anni inizino a sorgere una terribile vastità di tumori cutanei

Immagini

Fonti