La música latina es sumamente exigente, pues la gran mayoría de sus ritmos se estructuran sobre una par de células rítmicas, conocidas como “la clave”, en la cual una de las células es de dos golpes y la otra, de tres.

El ritmo que marcarán los demás instrumentos, tales como las congas, bongós, timbales, piano y hasta la misma voz, tiene que ir siguiendo el orden en que estén las dos células, ya sea primero la de tres y luego la de dos, o a la inversa.

El gran “drama” de los músicos que interpretan los géneros tropicales, está en saber ajustarse a esta regla, la cual es parte distintiva de la música y el sello que la identifica.

Sin embargo, muchas veces los músicos cometen errores a la hora de aplicarlas, o de manera consciente, rompen con la estructura y “cambian la clave”. En ocasiones esto es aceptado, dependiendo de la canción y el arreglo, pero en general, no es bien visto.

Esa característica es una de las razones por la que mucha gente ama el género, pero para otros esto es una complicación y, por lo tanto, no les gusta.

En los años 80, un músico de origen cubano, por muchos años radicado en Venezuela y dedicado profesionalmente a los jingles, decidió romper ese patrón. Sin duda, no era por falta de conocimientos, pues conocía a fondo la esencia y el significado de la clave, pero decidió lanzar un proyecto que fuera contra ese principio.

Latin music is extremely demanding, since most of its rhythms are structured on a pair of rhythmic cells, known as "la clave", in which one of the cells has two beats and the other has three.

The rhythm that will mark the other instruments, such as congas, bongos, timbales, piano and even the voice itself, has to follow the order in which the two cells are, either first the one of three and then the one of two, or the other way around.

The great "drama" of the musicians who play tropical genres is to know how to adjust to this rule, which is a distinctive part of the music and the seal that identifies it.

However, many times musicians make mistakes when applying them, or consciously break with the structure and "change the clave". Sometimes this is accepted, depending on the song and the arrangement, but in general, it is not well seen.

That characteristic is one of the reasons why many people love the genre, but for others this is a complication and, therefore, they don't like it.

In the 1980s, a musician of Cuban origin, for many years based in Venezuela and professionally dedicated to jingles, decided to break this pattern. Undoubtedly, it was not for lack of knowledge, since he knew in depth the essence and meaning of the clave, but he decided to launch a project that went against that principle.

Chamito Candela

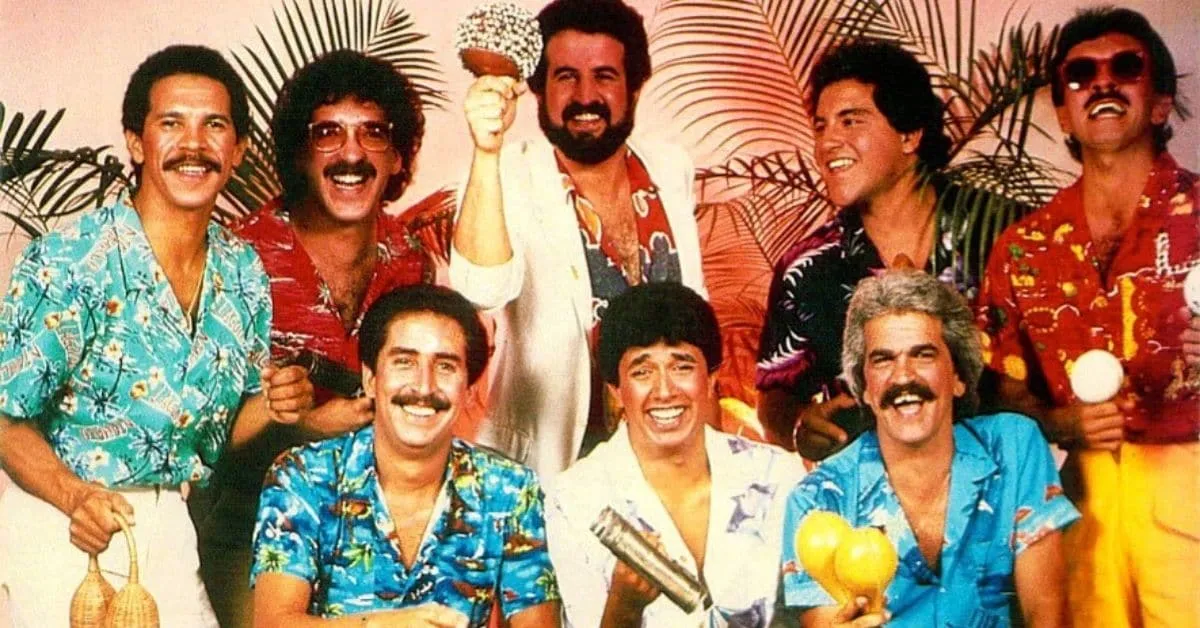

El nombre de ese músico es Alberto Slezynger y su proyecto se llamó Daiquirí. Su objetivo fue hacer una música que sonara tropical, alegre y sabrosa, pero que no tuviera la dependencia de la clave. Mantuvo, eso sí, el uso de los palitos que suelen marcarla y aunque estás marcaban la clave en todas las canciones, los arreglos, voces e instrumentos no se aferraban a su ritmo.

El éxito del grupo fue inmediato. La receptividad en la radio, en los medios de comunicación social, fue instantáneo y su presencia en fiestas se hizo obligatoria.

Una de las cosas más llamativas del éxito del grupo, fue que logró entrar en el gusto de muchas comunidades que hasta ese momento no disfrutaban los ritmos latinos. Daiquirí se volvió invitado regular en fiesta en zonas donde antes solo se escuchaba música llanera o vallenatos colombianos, llegó a público juvenil que andaba más con los sonidos rockeros y se hicieron asiduos en los eventos de las comunidades, judías, italianas y portuguesas, que con Daiquirí encontraron una forma de “bailar salsa”, según solían decir ellos mismos.

Un fenómeno musical que aún vive en el recuerdo de los que vivieron la época y que tienen a Alberto Slezynger a lanzar nuevamente un disco y volver a la palestra musical.

That musician's name is Alberto Slezynger and his project was called Daiquirí. His goal was to make music that sounded tropical, cheerful and tasty, but that did not depend on the clave. He kept, however, the use of the sticks that usually mark the clave, and although these marked the clave in all the songs, the arrangements, voices and instruments did not cling to its rhythm.

The group's success was immediate. Receptivity on the radio, on social media, was instantaneous and their presence at parties became mandatory.

One of the most striking things about the group's success was that it managed to enter into the taste of many communities that up to that moment did not enjoy Latin rhythms. Daiquirí became a regular guest at parties in areas where before only llanera music or Colombian vallenatos were heard, reached young audiences who were more into rock sounds and became regulars at events of Jewish, Italian and Portuguese communities, who with Daiquirí found a way to "dance salsa", as they used to say themselves.

A musical phenomenon that still lives on in the memory of those who lived through the era and that has led Alberto Slezynger to once again release an album and return to the musical limelight.

Vote la-colmena for witness

By @ylich

http://ylich.com

Spotify

Buy Ylich's "Pa' los bailadores" NFT at nfttunz.io