What is it about the University of Wisconsin and race? The administration’s recent decision to move a rock from view because a journalist referred to it with the N-word almost 100 years ago was goofy enough. But there has been more at the school in this vein.

This week a group including alumni, faith leaders, actors, and the N.A.A.C.P. wrote to University of Wisconsin officials asking them to repeal the tarring and feathering of an alumnus of the school, the renowned actor Fredric March. The letter, which was also sent to the Wisconsin governor, Tony Evers, and shared with me, decried the decisions to strip March’s name from theaters on the Madison and Oshkosh campuses, which the writers blamed on “social-media rumor and grievously fact-free, mistaken conclusions” about March.

March has been done a resounding wrong. I have no animus against the University of Wisconsin, but what we are seeing in these two sad episodes — the removal of the rock and the defenestration of March — is how antiracist “reckoning” can, if done without proper caution, detour into mere posturing, even at the cost of justice itself.

Fredric March is not the most famous of names among long-ago movie stars. But he attended the University of Wisconsin more than 100 years ago and went on to become as central in the old Hollywood firmament as Tom Hanks is today.

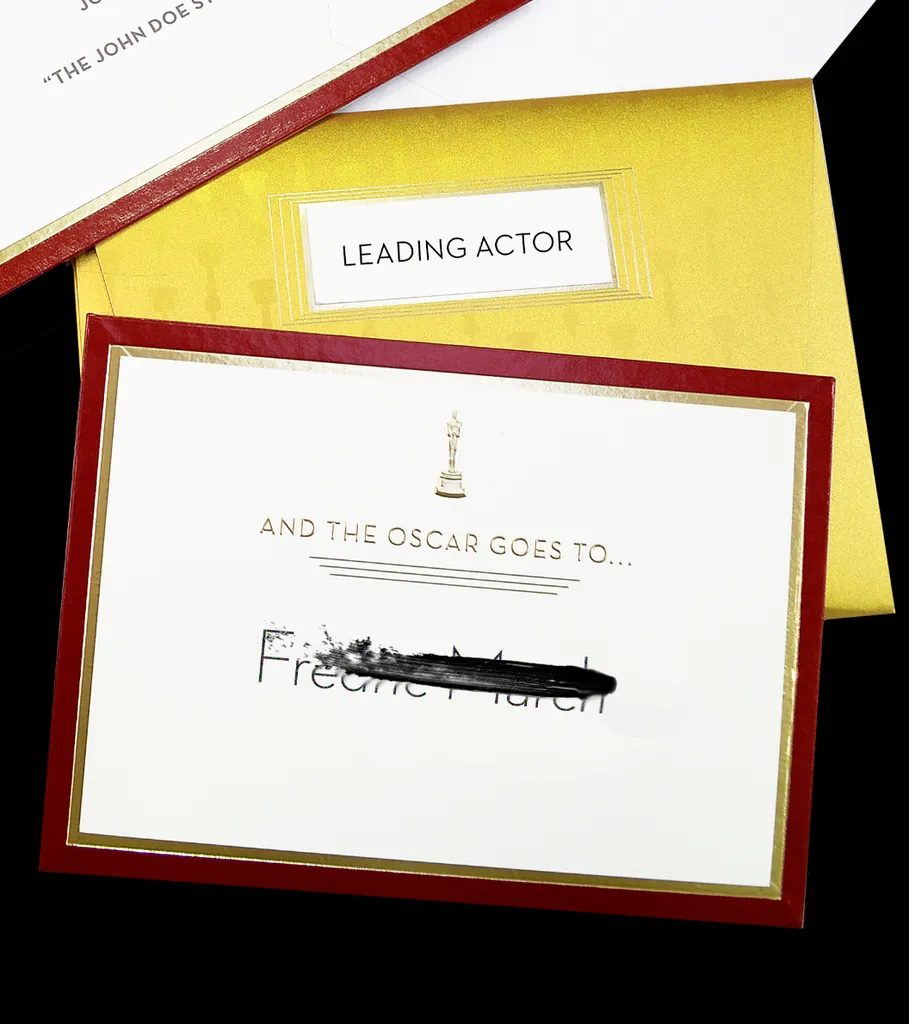

If you’re a fan of movie classics, you’ll most likely recognize him from his Academy Award-winning performance in “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” in 1931; in the original “A Star is Born” in 1937; as a middle-aged veteran in “The Best Years of Our Lives” in 1946, which earned him another Oscar; and as Willy Loman in the 1951 version of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman.” On stage he originated the role of James Tyrone on Broadway in Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” winning a Tony Award.

But no matter. Some wise people at the University of Wisconsin have decided that what we should know about Fredric March is that he belonged to a campus organization called the Ku Klux Klan as a lad. Except there is no evidence that his group was affiliated with the similarly named, but separate and notorious, K.K.K.

March wasn’t some white-hooded Klansman. Attention must be paid.

March’s alma mater once treasured him as a favorite son. They put his name on buildings. But in 2018, they took his name off the Fredric March Play Circle Theater on the Madison campus, and then last year the Oshkosh campus decided to take his name off a theater building as well.

The movement that sparked this Scarletization of March was led by students. Typical rhetoric was statements like this from one Madison student: “I cannot believe that my friends and I have been performing in a space named after someone who would have considered all of us to be lesser beings.” She added, “I find it so ironic that we are sharing our intersectional stories in a theater that honors a racist.”

Despite the conclusion of a report — commissioned by Madison’s chancellor — that there was no evidence linking the Ku Klux Klan organization March belonged to with its more widely known namesake, the student-driven campaign resulted in the removal of the actor’s name from that theater building. Throughout, there was apparently little or no investigation of what the man actually stood for.

But March was, to use our current term of art, a lifelong ally of Black people par excellence.

As the journalist George Gonis, who helped to write the recent letter in support of March, has uncovered in his research on the actor, March gave orations as a high schooler on what we would today call antiracism. In 1939, when the Daughters of the American Revolution barred Black contralto Marian Anderson from singing at Constitution Hall, he was not only one of the signatories on the famous protest letter, but attended Anderson’s protest concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, despite it meaning taking that night off from the Broadway play he was in. When Martin Luther King Jr. and Harry Belafonte were strategizing in the latter’s apartment in New York about civil rights efforts in Birmingham in 1963, March was there, too (King wrote a certain letter from jail soon thereafter). The next year, March was one of the white people who spoke on a national broadcast the NAACP sponsored in 1964 celebrating the 10th anniversary of Brown v. the Board of Education.

This is a Klansman???

Hardly. It just happened that in 1919 into 1920 March briefly belonged to an organization that happened to also be called Ku Klux Klan.

Yes, I know — but wait. It was a student interfraternity organization. The Ku Klux Klan of revolting memory had emerged at first amid Reconstruction and then flamed out. The later 20th century Klan emerged gradually in the wake of the racist film “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915, and only became a national phenomenon starting in 1921. In Wisconsin in 1919, when March was inducted into his group, it was possible to have never heard of the Ku Klux Klan that was later so notorious.

We can’t know whether this group modeled this name after the Ku Klux Klan organization depicted in “The Birth of a Nation.” But what we do know is that there is no evidence that their mission had anything to do with racism, and that when the “real” Klan made its way to campus in 1922, the organization March had joined (but left in 1920) immediately dissociated itself from that group and changed its name.

The name of the campus’s Ku Klux Klan seems to have been an accident. Clumsy, probably. The boys may not have thought of the “real” Klan as significant enough players in 1919 to merit avoiding the same name, and just liked the sound of it because of the sequential k’s and such. There is no record of this organization doing or supporting anything racist — and let’s recall that in this era, racism was thought of as so acceptable in conventional expression that one could in a newspaper casually refer to a big rock with a racist epithet for Black people.

Some antiracist activists may see this as nit-picking. They may argue that these young people must have known there was a racist Ku Klux Klan and didn’t care enough to change the organization’s name, and that this evidences a kind of racism in itself.

These are reasonable points. But against them, to seek a fair-minded assessment rather than a Star Chamber, we must note that in addition to what I wrote above, March’s life also included battling McCarthyite red-baiting (to which he was subjected) and anti-Semitism. His wife, the actress Florence Eldridge, was a lifelong prominent progressive. He was friends his whole adult life with the philosopher Max Otto, who was a Unitarian-Unversalist, a group famously aligned with the civil rights movement even today.

Even Madison’s chancellor, Rebecca Blank, has written that March had “fought the persecution of Hollywood artists, many of them Jewish, in the 1950s by the House Un-American Activities Committee” and that March “took actions later in life to suggest (he) opposed discrimination.” Oshkosh’s chancellor, Andrew Leavitt, acknowledged this history too, and said “there is no evidence to show that the UW-Madison group March belonged to was linked to the national movement of the Ku Klux Klan in its time.” But Leavitt said people on campus felt “shock and pain” over learning about March’s involvement in the similarly named group, and said: “I no longer possess — and this institution should reject — the privilege of nuancing explanations as to how a person even tangentially affiliated with an organization founded on hate has his name honorifically posted on a public building.”

Could March have possibly been a progressive but a racist one? Then how about the fact that Canada Lee, a Black activist actor, considered him an ally? Or that after the Daughters of the American Revolution episode, March often socialized with Marian Anderson? Or that now, people appalled at March’s treatment and writing in support include Black figures such as King comrade Dr. Clarence B. Jones, Langston Hughes’ biographer Arnold Rampersad, and actors Louis Gossett Jr. and Glynn Turman? Not to mention, white though he was, lifelong leftist activist Ed Asner just before his passing?

To take the measure of the man, rather than engage in 21st century American virtue signaling, makes the case for Fredric March as a racist rather hopeless.

Yet some may take in all of the above and still feel that March has been treated fairly, thinking apparently March went from antiracist teen orator to a spell as a Klansman collegiate bigot to a life marked by antiracist activism. Our interest is less in engaging how plausible that is than in filleting March to show that we know that racism is bad. We must do so by fashioning a fantastically know-nothing interpretation of a mere nine months of the man’s life and walk on proud of our antiracist spirits.

But I take the liberty of assuming that those who truly feel this way constitute a set-jawed huddle of people studiously impervious to explanation in favor of a battle pose.

I must take one more liberty and venture: That is not the way most of us think, including those of us quite agonized over how to turn a corner on race in America. This witch-burning mentality is something most of us less concur with than fear. These “Crucible” characters (Arthur Miller helps us again) get their way by threatening to shame us the way they are shaming the latest transgressor.

The students who got March’s name taken off those buildings made a mistake, as did the administrators who again caved to weakly justified demands, seemingly too scared of being called racists to take a deep breath and engage in reason.

The University of Wisconsin must apologize to March and his survivors. His name should be restored to both of the theaters now denuded of his name, including the Madison building, which he in fact helped bring into being and funded the lighting equipment even before the building was named after him.

This must happen in the name of what all involved in this mistake are committed to: social justice — which motivated March throughout his life.