How Mexican is Yucatán?

Mérida is the capital of Yucatán. The federal entity has two million inhabitants, more than half of whom live in the greater area around the city, i.e. more than one million.

Mexico is a wonderful destination, but at the same time difficult to understand. In Mérida, too, the visitor notices great conflicts that divide the country: centralist claims and regional aspirations for independence, colonial European culture and indigenous traditions.

When locals in Mérida talk about Mexico, they usually don’t mean Yucatán, but Mexico City, or the metropolitan region with its 22 million inhabitants, which may feel as far away as, let us say, New York. When I asked our bus driver where he was from, he said: »From Mexico«. But he meant: »Not from Yucatán«.

Wie mexikanisch ist Yucatán?

Mérida ist die Hauptstadt von Yucatán. Der mexikanische Bundesstaat hat zwei Millionen Einwohner, davon lebt über die Hälfte im Ballungsraum rund um die Stadt, also mehr als eine Million.

Mexiko ist ein wunderbares Reiseziel, gleichzeitig aber auch schwer zu verstehen. Auch in Mérida findet der Besucher die großen Konflikte, die das Land spalten: zentralistische Ansprüche und regionales Streben nach Unabhängigkeit, koloniale europäische Kultur und einheimische Traditionen.

Wenn Einheimische in Mérida von Mexiko sprechen, meinen sie gewöhnlich nicht Yucatán, sondern Mexiko-City beziehungsweise die Metropolregion mit ihren 22 Millionen Einwohnern, die gefühlt unter Umständen genauso weit weg liegt wie, sagen wir, New York. Als ich unseren Busfahrer fragte, wo er her käme, sagte er: »Aus Mexiko«. Auf Nachfrage kam heraus, was er damit meinte, nämlich: »Nicht aus Yucatán«.

View over the rooftops of Mérida: in the background, the cathedral and the reddish tower of the town hall. Mérida is certainly not idyllic, but nevertheless beautiful and above all very lively.

Blick über die Dächer Méridas: Im Hintergrund die Kathedrale und der rötliche Turm des Rathauses. Mérida ist gewiss nicht idyllisch, aber trotzdem schön und vor allem sehr lebendig.

Cathedral of Mérida in the evening: During rush hour roaring traffic squeezes through narrow streets.

Die Kathedrale von Mérida am Abend: Während der Rush Hour zwängt sich ein brüllender Verkehr durch enge Straßen.

Ti’ho’ was the name of the Maya settlement on whose ruins Mérida stands. Ti’ho’ was as important as other religious centres, for example Chichén Itza or Izamal. When the Spanish conquistadors saw the massive Mayan temples in 1542, they felt reminded of the Roman buildings in Mérida, Spain. This is how the ancient Maya city got a new name.

Mérida has been the seat of a bishop since 1561. In 1911, the Pope even elevated the bishopric to an archdiocese. The bishop’s church »Catedral de Ildefonso« was built between 1561 and 1598, using the stones of Mayan buildings, just like Izamal, one of the oldest monasteries in the New World.

Ti’ho’ hieß die Siedlung der Maya, auf deren Trümmern Mérida steht. Ti’ho’ war ähnlich bedeutend wie andere religiöse Zentren, zum Beispiel Chichén Itza oder Izamal. Als die spanischen Eroberer 1542 vor den gewaltigen Tempelbauten der Maya standen, fühlten sie sich an die römischen Bauwerke im spanischen Mérida erinnert. So kam die alte Maya-Stadt zu einem neuen Namen.

Mérida ist seit 1561 Sitz eines Bischofs. 1911 erhob der Papst das Bistum sogar zur Erzdiözese. Die Bischofskirche »Catedral de Ildefonso« wurde zwischen 1561 und 1598 gebaut, und zwar aus den Steinen der Maya-Bauten, genau wie Izamal, eines der ältesten Klöster der neuen Welt.

Plaza Grande, the centre of Mérida, in the background Palacio Municipal, the city hall.

Plaza Grande, das Zentrum Méridas, im Hintergrund der Palacio Municipal, das Rathaus.

Most of the city’s historic buildings are located around the central square, the Plaza Grande or Plaza de la Independencia. The town hall (Palacio Municipal) was built from 1735 onwards. In 1821, the independence of the state of Yucatán from Mexico was proclaimed from the veranda on the first floor of the building.

Rund um den zentralen Platz, die Plaza Grande oder auch Plaza de la Independencia, findet man die meisten historischen Gebäude der Stadt. Das Rathaus (Palacio Municipal) entstand ab 1735. Im Jahr 1821 wurde von der Veranda im ersten Stock des Gebäudes die Unabhängigkeit des Bundesstaates Yucatán von Mexiko ausgerufen.

Courtyard of the Palacio de Gobierno, seat of the regional government of Yucatán.

Innenhof des Palacio de Gobierno, Sitz der Landesregierung von Yucatán.

The Palacio de Gobierno is freely accessible to visitors. It stands opposite the cathedral on the north side of the central square. The neoclassical building was completed in 1892 and is the seat of the regional government of Yucatán. From 1971 to 1974, Fernando Castro Pacheco painted the walls inside with scenes from the history of Yucatán.

The official name of the federal state is »Estado Libre y Soberano de Yucatán«, »Libre y Soberano«, free and sovereign, which is meant quite seriously. In the course of Mexico’s independence, the notables of Yucatán tried several times to break away from the central government in Mexico City.

The last attempt was made in 1841 and failed because of the Caste War, which began in 1847 and only ended in 1901: the rulers in Mérida were ultimately more afraid of rebellious Maya than of the central government in Mexico, from which they could expect support through the army.

Independence efforts until now are an issue. Further south in Chiapas, the Zapatistas have been fighting for the rights of the indigenous Maya since 1994. There exist still areas today that cannot be controlled by the central government.

Der für Besucher frei zugängliche Palacio de Gobierno steht gegenüber der Kathedrale an der Nordseite des zentralen Platzes. Das Gebäude im neoklassizistischen Stil wurde 1892 fertiggestellt und ist Sitz der Landesregierung von Yucatán. 1971 bis 1974 bemalte Fernando Castro Pacheco die Wände im Inneren mit Szenen aus der Geschichte Yucatáns.

Der offizielle Name des Bundesstaats lautet »Estado Libre y Soberano de Yucatán«, »Libre y Soberano«, frei und souverän, das ist durchaus ernst gemeint. Im Zuge der Unabhängigkeit Mexikos gingen die Notabeln Yucatáns immer wieder eigene Wege und versuchten mehrfach, sich von der Zentralregierung in Mexiko-City zu lösen.

Der letzte Versuch erfolgte 1841 und scheiterte am Kastenkrieg, der 1847 begann und erst 1901 formell endete: Die Regierenden in Mérida hatten letztlich doch mehr Angst vor aufständischen Maya als vor der Zentralregierung in Mexiko, von der sie Unterstützung durch die Armee erwarten durften.

Streben nach Unabhängigkeit ist im Grunde immer noch ein Thema. Weiter südlich in Chiapas kämpfen seit 1994 Zapatisten für die Rechte der indigenen Maya. Dort gibt es bis heute Gebiete, die nicht von der Zentralregierung kontrolliert werden können.

Building from the beginning of Spanish rule in Yucatán: Casa Montejo on the south side of the Plaza Grande, today a bank.

Gebäude vom Beginn der spanischen Herrscharft in Yucatán: Casa Montejo an der Südseite der Plaza Grande, heute Sitz einer Bank.

The conquest of Yucatán from 1528 to 1542 was to some extent a family affair. To confuse us, three protagonists bear exactly the same name: Francisco de Montejo.

Mérida was founded on 6 January 1542 by Francisco de Montejo the Younger (»El Mozo«, 1508–1565). His father, Francisco de Montejo the Elder (»El Adelantado«, 1479–1553), began subduing Yucatán for the Spanish crown in 1528. The third in the alliance was Francisco de Montejo the Nephew (»El Sobrino«, 1514–1572), who founded Valladolid in 1543.

Die Eroberung Yucatáns 1528 bis 1542 war bis zu einem gewissen Grad eine Familienangelegenheit. Um die Nachwelt zu verwirren, tragen drei Protagonisten genau den gleichen Namen: Francisco de Montejo.

Mérida wurde am 6. Januar 1542 von Francisco de Montejo dem Jüngeren (»El Mozo«, 1508–1565) gegründet. Sein Vater, Francisco de Montejo der Ältere (»El Adelantado«, 1479–1553), begann 1528 damit, Yucatán für die spanische Krone zu unterwerfen. Der Dritte im Bunde war Francisco de Montejo der Neffe (»El Sobrino«, 1514–1572), der 1543 Valladolid gründete.

Momument Dedicated to Nation

From the central Plaza Grande with Cathedral, Palacio Municipal, Palacio del Gobierno and Casa Montejo, you reach the Paseo de Montejo, which leads directly to the Monumento a la Patria, three kilometres away. The monument stands in the middle of a busy roundabout. If you are lucky, a policeman is there to stop traffic for tourists.

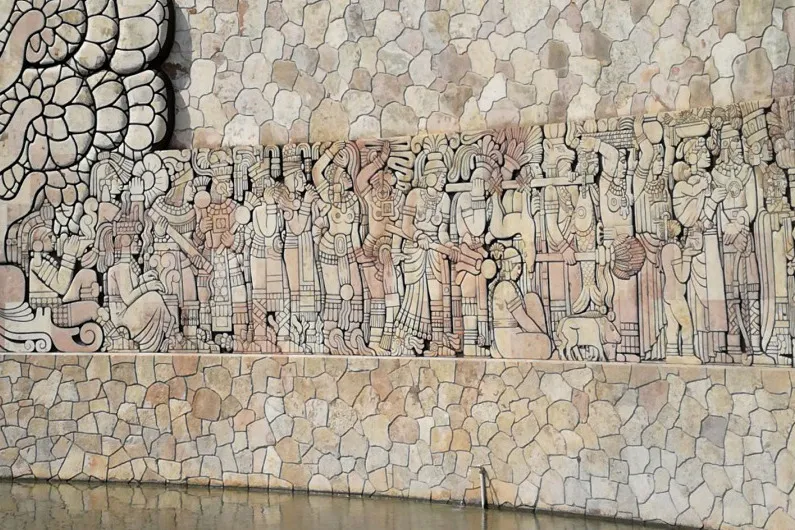

The Monumento a la Patria was unveiled on 23 April 1956. The outer diameter is 40 metres, the height up to 14 metres. The monument was designed by Rómulo Rozo. The sculptor came from Colombia, but had spent a large part of his life in Mexico.

Rómulo Rozo worked on the Monumento a la Patria for eleven years. The friezes show the history of Mexico from the founding of Tenochtitlán by the Aztecs to the middle of the 20th century. The woodcut style is called »decó indigenista neomaya« – so probably an »Art Decó« in mayan style. Unfortunately, I could not find out which stone was used for the monument.

Denkmal für das Vaterland

Von der zentralen Plaza Grande mit Kathedrale, Palacio Municipal, Palacio del Gobierno und Casa Montejo gelangt man zum Paseo de Montejo, der direkt zum drei Kilometer entfernten Monumento a la Patria führt. Das Denkmal steht in der Mitte eines stark befahrenen Kreisels. Wenn man Glück hat, ist ein Polizist da, der für die Touristen kurz den Verkehr anhält.

Das Monumento a la Patria wurde am 23. April 1956 enthüllt. Der äußere Durchmesser beträgt 40 Meter, die Höhe bis zu 14 Meter. Gestaltet wurde das Denkmal von Rómulo Rozo. Der Bildhauer stammte aus Kolumbien, hatte aber einen großen Teil seines Lebens in Mexiko verbracht.

Rómulo Rozo arbeitete elf Jahre am Monumento a la Patria. Die Friese zeigen die Geschichte Mexikos von der Gründung Tenochtitláns durch die Azteken bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Der holzschnittartige Stil wird als »decó indigenista neomaya« bezeichnet – also wohl ein »Art Decó« im Stil der Maya. Leider konnte ich nicht in Erfahrung bringen, welcher Stein für das Denkmal verwendet wurde.

The Monumento a la Patria encloses a semicircular fountain symbolising Lake Texcoco.

Das Monumento a la Patria umschließt einen halbkreisförmigen Brunnen, der den Texcoco-See symbolisiert.

In the centre of the monument are an eagle and a snake, the symbol derived from the Aztecs, which can also be found on the flag of Mexico: where an eagle fights with a snake, the Aztecs were to build Tenochtitlán. Inside the monument, which has a total diameter of 40 metres, is a fountain symbolising Lake Texcoco. Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztecs, was located on several islands in the once huge lake. The balustrade delimiting the fountain comprises 31 small columns with the coats of arms of the Mexican states. In the background under the flag is a ceiba, the sacred tree of the indigenous people.

Im Zentrum des Denkmals stehen Adler und Schlange, das von den Azteken abgeleitete Symbol, das auch auf der Fahne Mexikos zu finden ist: Dort, wo ein Adler mit einer Schlange kämpft, sollten die Azteken Tenochtitlán bauen. Im Inneren des Denkmals von insgesamt 40 Meter Durchmesser ist ein Brunnen, der den Texcoco-See symbolisiert. Tenochtitlán, die Hauptstadt der Azteken, lag auf mehreren Inseln in dem einst riesigen See. Die Balustrade zur Begrenzung des Brunnens umfasst 31 kleine Säulen mit den Wappen der mexikanischen Bundesstaaten. Im Hintergrund unter der Fahne ist eine Ceiba dargestellt, der heilige Baum der Ureinwohner.

An Aztec prophecy said: where an eagle sits on an opuntia and fights with a snake, they should make their capital.

Eine Weissagung der Azteken besagte: Dort, wo ein Adler auf einer Opuntie sitzt und mit einer Schlange kämpft, sollten sie ihre Hauptstadt bauen.

Rómulo Rozo created a panorama of over 300 figures to illustrate the history of Mexico from the founding of Tenochtitlán to the present day.

Rómulo Rozo schuf ein Panorama aus über 300 Figuren, um die Geschichte Mexikos von der Gründung Tenochtitláns bis in die Gegenwart zu illustrieren.

Ramps lead to the outside of the monument. Warriors apparently are standing guard.

Rampen führen zur Außenseite des Denkmals. Offenbar stehen rechts und links Krieger Wache.

On the outside: sculpture of a female figure with indigenous features.

Auf der Außenseite: Skulptur einer weiblichen Figur mit indigenen Zügen.

On the back outside of the monument, a huge female figure looks towards the city centre. Clothes and jewellery correspond to Mayan traditions. Jaguar warriors crouch at her feet on the right and left.

Rómulo Rozo, the creator of the monument, wanted to set a sign for the unity of Mexico and against Yucatán separatism. He is reported to have said: »I built the first altar for the fatherland in Mérida so that national sentiment would eradicate the ideas of Yucatecan separatism.« Did Rómulo Rozo achieve this?

Auf der rückwärtigen Außenseite des Denkmals blickt eine monumentale Frauengestalt Richtung Stadtzentrum. Kleidung und Schmuck entsprechen den Traditionen der Maya. Zu ihren Füßen kauern rechts und links Jaguar-Krieger.

Rómulo Rozo, der Schöpfer des Denkmals, wollte ein Zeichen für die Einheit Mexikos und gegen den Separatismus Yucatáns setzen. Er soll gesagt haben: »Ich habe in Mérida den ersten Altar für das Vaterland errichtet, damit das Nationalgefühl die Ideen des yucatecischen Separatismus auslöscht.« Ob Rómulo Rozo das erreicht hat?

Coat of arms of Mérida: lion and city gate. On the lower right, a chacmol as a symbol of the Maya heritage.

Wappen von Mérida: Löwe und Stadttor. Rechts unten ein Chacmol als Symbol für das Erbe der Maya.

Habsburg in Mexico

In October 1863 Maximilian, the younger brother of the Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph I, received a delegation from Mexico at his castle near Trieste. The Mexicans offered the Crown Prince nothing less than the Mexican Imperial Crown._

Ein Habsburger in Mexiko

Im Oktober 1863 empfing Maximilian, der jüngere Bruder des Habsburger Kaisers Franz Jospeh I., auf seinem Schloss bei Triest eine Delegation aus Mexiko. Die Mexikaner boten dem Kronprinz nichts weniger als die mexikanische Kaiserkrone an.

Detail of the Monumeno a la Patria: the Habsburg Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico from 1864 to 1867, next to his wife, Princess Charlotte of Belgium.

Detail vom Monumeno a la Patria: der Habsburger Maximilian I., 1864 bis 1867 Kaiser von Mexiko, neben seiner Frau, Prinzessin Charlotte von Belgien.

How could a Habsburg become Emperor of Mexico?

When the Mexicans succeeded in gaining independence from the Spanish crown in 1821 after a long war, the country had huge debts to the major European powers. In 1861, President Benito Juarez suspended payments. This prompted Napoleon III to intervene militarily. Napoleon’s ultimate goal was to expand French influence in the New World.

Emperor Maximilian was merely a pawn in this game. He had no clue about the conditions in Mexico, and even believed he could do good with his liberal views. In reality, he had no choice but to finance the French occupation forces, make common cause with the conservative circles in the country and continue to service the foreign debt, precisely the task Napoleon III had assigned him.

Against all odds, Benito Juarez succeeded in keeping the French troops at bay. At the same time, the USA intervened, which was once again able to act after the end of the War of Secession. Neither the USA nor any other state on American soil wanted to accept the influence of a major European power like France.

Together with his last loyal followers, Maximilian I was captured, sentenced to death by a summary court martial and executed on 19 June 1867. In the face of death, he slipped gold pieces to the soldiers of the firing squad and asked them to aim at his chest so that his face would remain unharmed.

After a long odyssey, the body was brought to Europe and buried in 1868 in the Capuchin Crypt (»Kapuzinergruft«), the burial place of the Habsburgs in Vienna. Maximilian’s wife Charlotte went insane, probably as a result of the events, and did not die until 1927.

Wie konnte ein Habsburger Kaiser von Mexiko werden?

Als es den Mexikanern 1821 nach langem Krieg gelungen war, die Unabhängigkeit von der spanischen Krone zu erkämpfen, hatte das Land bei den europäischen Großmächten gewaltige Schulden. 1861 setzte Präsident Benito Juarez die Zahlungen aus. Dies nahm Napoleon III. zum Anlass, militärisch zu intervenieren. Napoleons Ziel war letztlich, den französischen Einfluss in der Neuen Welt auszubauen.

Kaiser Maximilian war lediglich eine Figur in diesem Spiel. Er hatte keinen Schimmer von den Verhältnissen in Mexiko, glaubte sogar, mit seinen liberalen Ansichten Gutes bewirken zu können. In der Realität blieb ihm nichts anderes übrig, als die französischen Besatzungstruppen zu finanzieren, mit den konservativen Kreise im Land gemeinsame Sache zu machen und die Auslandsschulden weiter zu bedienen, genau die Aufgabe, die Napoleon III. ihm zugedacht hatte.

Benito Juarez gelang wider allem Erwarten, die französischen Truppen in Schach zu halten. Gleichzeitig schalteten sich die USA ein, die nach dem Ende des Sezessionskrieg wieder handlungsfähig waren. Weder die USA noch irgendein andere Staat auf amerikanischem Boden wollte den Einfluss einer europäischen Großmacht wie Frankreich hinnehmen.

Zusammen mit seinen letzten Getreuen wurde Maximilian I. gefangen genommen, durch ein Standgericht zum Tod verurteilt und am 19. Juni 1867 hingerichtet. Im Angesicht des Todes steckte er den Soldaten des Erschießungskommandos Goldstücke zu und bat sie, auf die Brust zu zielen, damit sein Gesicht unversehrt bleibe.

Der Leichnam wurde nach längerer Odyssee nach Europa überführt und 1868 in der Kapuzinergruft beigesetzt, der Grabstätte der Habsburger in Wien. Maximilians Frau Charlotte wurde, wohl infolge der Ereignisse, wahnsinnig und starb erst 1927.

Copper coffin of Maximilian I in the Capuchin Crypt in Vienna. Photo: © Simon Zappe, Kapuzinergruft.

Kupfersarg Maximilans I. in der Kapuzinergruft in Wien. Bild: © Simon Zappe, Kapuzinergruft.

In April 2018, I visited the Capuchin Crypt in Vienna, the burial place of the Habsburgs. The atmosphere here is appropriately sombre. Only on the coffin of the beloved Empress Sissie is a bouquet of roses. But then this: in front of the copper coffin of Maximilian I, flowers, pictures, Mexican flags, a colourful mixture of devotional objects pile up.

Are there Mexicans who pay their last respects to their emperor? That appears to be the case. There is something comforting about this: Maximilian I failed all along the line. But for all the suffering he brought upon Mexico, it seems that his good intentions and honourable ways have not been forgotten.

Im April 2018 besuchte ich die Kapuzinergruft in Wien, die Grabstätte der Habsburger. Hier herrscht eine angemessen düstere Atmosphäre. Nur auf dem Sarg der beliebten Kaiserin Sissie liegt ein Rosenstrauß. Doch dann das: Vor dem Kupfersarg Maximilians I. häufen sich Blumen, Bildchen, mexikanische Fähnchen, ein buntes Gemisch aus Devotionalien.

Sind es Mexikaner, die hierher pilgern und ihrem Kaiser die letzte Ehre erweisen? Alles spricht dafür. Das hat etwas Tröstliches: Maximilian I. ist auf der ganzen Linie gescheitert. Aber bei allem Leid, das der über Mexiko gebracht hat, scheint es, dass man seine guten Absichten und ehrenhafte Art nicht vergessen hat.

Sources and Thanks

In the Spanish Wikipedia there is a very detailed and good description of the Monumento a la Patria. The quote from Rómulo Rozo translated above also comes from there: »He levantado en Mérida el primer altar a la patria para borrar del espíritu nacional las ideas sobre el separatismo yucateco. La patria es de todos y para todos.«

There is somewhat contradictory information on Maximilian I in Wikipedia and on the blog for the website of the Capuchin Crypt. I consider the blog to be the more reliable source. A big thank you to the staff of the Capuchin Crypt for providing me with the picture of Maximilian's coffin with the devotional objects.

Quellen und Dank

In der spanischen Wikipedia gibt es eine sehr ausführliche und gute Beschreibung des Monumento a la Patria. Von dort stammt auch das oben übersetzte Zitat von Rómulo Rozo: »He levantado en Mérida el primer altar a la patria para borrar del espíritu nacional las ideas sobre el separatismo yucateco. La patria es de todos y para todos.«

Zu Maximilian I. findet man teils etwas widersprüchliche Angaben in Wikipedia und auf dem Blog zur Webseite der Kapuzinergruft. Den Blog halte ich für die verlässlichere Quelle. Ein herzliches Dankeschön an die Mitarbeiter der Kapuzinergruft, die mir das Bild vom Sarg Maximilians mit den Devotionalien zur Verfügung stellten.

Chacmol, replica in front of hotel in Valladolid: »See you later!«

Chacmol, Nachbildung vor einem Hotel in Valladolid: »See you later!«