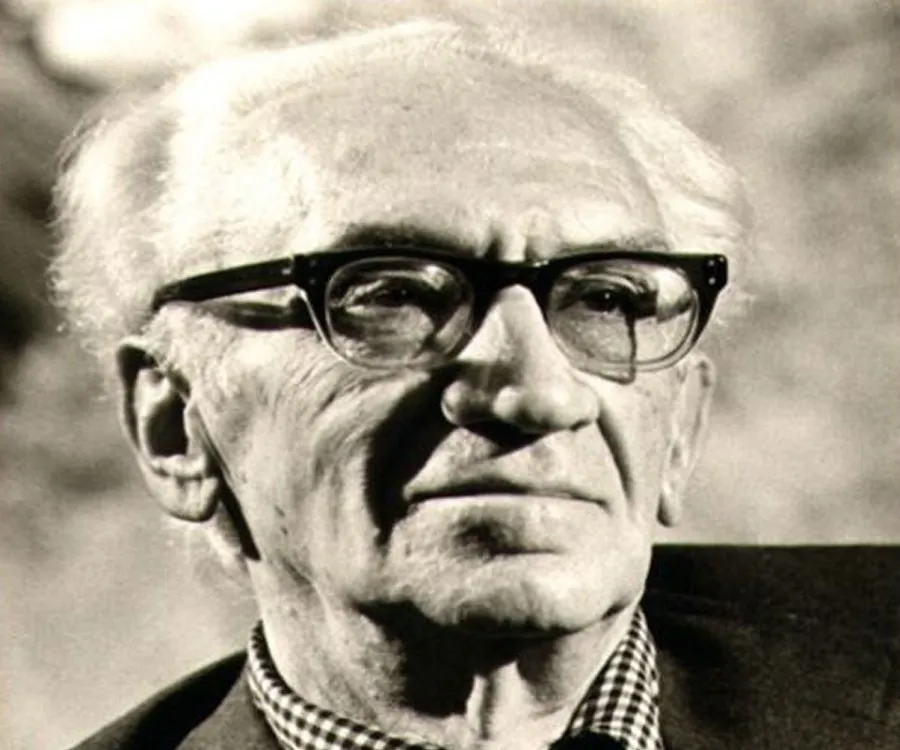

Recently I came across some quality research on Steemit by @anotherjoe on the Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Anyone who has been following my contributions to Steemit will know that this sort of thing is right up my street. For more than a years now I have been ploughing a lonely furrow in the field of Irish history, but my perspective on ancient chronology grew out of my reading of Immanuel Velikovsky and his disciples.

The Bible lies at the heart of Velikovsky’s pioneering research, and out of that research came the Short Chronology. This work in progress has been honed and refined over the past forty years by scholars like Lynn E. Rose, Charles Ginenthal, Gunnar Heinsohn, and Emmet Sweeney, among others. In the process, some of Velikovsky’s most cherished beliefs have been set aside and others have been significantly modified. I briefly described the Short Chronology in my very first article on Steemit—Ireland and the Short Chronology—but a quick review would not be out of place here.

The Short Chronology

The Short Chronology is, as I said, a work in progress. Even the leading adherents of this model do not see eye-to-eye on every detail. Nevertheless, a broad consensus has been reached, which may be outlined as follows;

The last Ice Age was ended by a global catastrophe which occurred around 1500 BCE

This catastrophe devastated human civilization and essentially reset everything to the Stone Age

The great civilizations of the Ancient World rose from the ashes some centuries after the catastrophe, probably all within a few hundred years of one another

In southern Mesopotamia, Chaldaean (ie Sumerian) city states began to appear around 1300 BCE

In Egypt, the first dynasties arose around the same time

In India, the Indus-Valley Civilization followed suit

In China, civilization reappeared in the valley of the Yellow River with the Xia or Shang dynasty

In Mesoamerica, the Olmecs led the way

In South America, the Norte Chico Civilization was the first to emerge

This paradigm involves a radical shortening and realignment of the traditional chronological framework. Human history—in its current phase, at least—is not nearly as old as we have been taught.

The Bible

So, what has this to do with the Bible? Quite a lot, actually. The simple fact is that the traditional chronological framework sits on a foundation of Biblical scholarship. Modern historiography dates from the Age of Enlightenment, and most of its leading lights were secular scholars—several were even unashamed atheists. But by the time these rationalists and freethinkers began their studies, the general framework of ancient history and its chronology had already been established by the religious scholars who had preceded them. These religious scholars—Christian clergymen for the most part—drew their inspiration from both the Bible and the historians of the Classical world.

Long before modern methods of historiographical research had been developed, and centuries before the scientific discipline of archaeology had been introduced, the broad brushstrokes of ancient history were already in place. In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte exhorted his troops before the Battle of the Pyramids by pointing towards the pyramids of Giza and solemnly announcing:

Soldats, songez que du haut de ces pyramides quarante siècles vous regardent. [Remember, Soldiers, that from those monuments forty centuries look down upon you.] (Beauharnais 41)

How did Napoleon know that the pyramids were built around 2200 BCE?

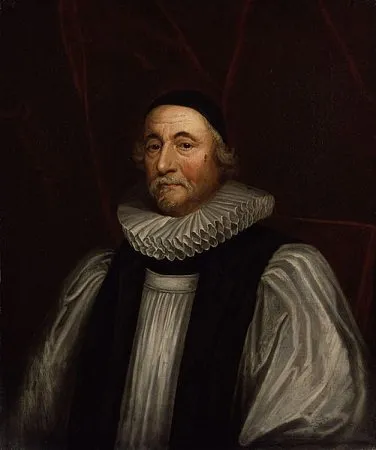

Archbishop Ussher

It was a compatriot of mine, James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, who consolidated the foundations of our modern chronology. In Ireland there was already a well-established custom of compiling annals. How much the poorer our literary heritage would be without the Annals of the Four Masters, or the Annals of Ulster, or the Annals of Inisfallen, or the Annals of Tigernach, or the Annals of Connacht, or the Annals of Loch Cé, or a dozen other sets of annals I could name. But Archbishop Ussher was not satisfied with treading in the footsteps of his Popish predecessors: he set himself the much more daunting challenge of compiling the annals of the whole world.

Drawing upon a wealth of written traditions—the Bible, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Arrian, and dozens of minor scholars—he spent perhaps ten years of his life compiling the monumental Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti, una cum rerum Asiaticarum et Aegyptiacarum chronico, a temporis historici principio usque ad Maccabaicorum initia producto. (Annals of the Old Testament, Deduced from the First Origins of the World to the Beginning of the Maccabees, Together with a Chronicle of Asiatic and Egyptian Matters), which was published in 1650. A continuation, Annalium pars posterior (The Latter Part of the Annals), appeared in 1654 and brought the annals down to AD 73. The first English translation of the complete work was published in 1658. Recently, this translation was updated for the modern world by Larry and Marion Pierce as The Annals of the World.

It was in this mighty tome that Ussher famously dated of the Creation of the World to 4004 BC. Ussher’s chronology built on the pioneering efforts of his predecessors—eg Joseph Justus Scaliger and John Lightfoot—and cemented the Biblical timeframe in place. Since then, almost every mainstream scholar who has studied the history of the ancient world unquestioningly accepts Ussher’s timescale, more or less: civilization arose in the Near East in the fourth millennium BC, and the succession of kingdoms and empires followed the scheme laid down in his Annals of the World.

Ussher’s chronology relies entirely on written records and testimonies, not on scientific or archaeological evidence. Ussher himself accepted the infallibility of Holy Scripture: this was the very bedrock on which he raised his mighty edifice. But can we trust it? Or, rather, should we trust it?

Faking History

The deliberate fabrication of history is not a new phenomenon. Long before the emergence of our modern Orwellian world, rulers and their propagandists had been making shit up and passing it off as the real thing. And for every premeditated lie that has found its way into our history books, there is probably at least one untruth that owes its origin more to human error than to human deceit. This is why scientific evidence must complement documentary evidence, and why both must be subjected to proper scrutiny.

Take, for example, a celebrated case in which two rival dynasties competed with each other for primacy and preeminence. After the death of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian Empire was fragmented among his successors, the Diadochi. Among these were Ptolemy, who became the ruler of Egypt, and Seleucus, who inherited Babylonia. The two dynasties established by these men—the Ptolemies and the Seleucids—were bitter rivals. Between 274 and 168 they fought a series of six Syrian Wars for control of Coele-Syria (loosely the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon and adjacent territories). The first of these wars broke out during the reigns of Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Antiochus I Soter, each of whom was the second ruler of his dynasty.

Ptolemy was victorious on the battlefield, but Antiochus opened a new front on papyrus. It was during his reign (285-261), allegedly, that Berossus (or Berossos), a Chaldaean priest of Marduk in Babylon, wrote a history of Chaldaea in three books. Berossus dedicated this Chaldaica (also known as the Babyloniaca) to Antiochus, who possibly commissioned it.

Not to be outdone, Ptolemy retaliated by commissioning a learned Egyptian priest to write a history of Egypt. Manetho (or Manethon) is thought to have lived shortly after Berossus. He was a priest at Heliopolis in Lower Egypt. He dedicated this history of his native land, Aegyptiaca, to Ptolemy II, who reigned from 285 to 246.

Now, we do not actually know that these two histories were commissioned by royal decrees, as I have described here: it is merely a speculation. But this is not my speculation: it is that of scholars in the field:

The works of Manetho and Berossos may be interpreted as an expression of the rivalry of the two kings, Ptolemy and Antiochus, each seeking to proclaim the great antiquity of his land. (Waddell x)

Both Berossus and Manetho wrote histories of their respective nations in three books, which they then dedicated to the reigning monarch. Even the titles by these works were commonly known—Babyloniaca and Aegyptiaca—are similar. It is hard not to see them as rivals who were hired to do a job. George Syncellus, a Byzantine historian of the early 9th century, had no doubts on the matter:

... it has been also clearly demonstrated at the same time that what has been written about the Egyptian dynasties by Manetho of Sebennytos to Ptolemy Philadelphos is full of untruth and fabricated in imitation of Berossos at about the same time or a little later than him ... If you pay close attention to the two tables given below, you will be immediately and utterly convinced that the thinking of both of them, as was stated above, is contrived, the thinking both of Berossos and of Manetho, who seek to glorify their own nation, the one the nation of the Chaldaeans, the other that of the Egyptians. (Adler & Tuffin 22)

Put simply, Berossus and Manetho were employed by their new masters to create fake histories of their nations that reflected glory onto the Macedonian rulers. It was in their interests to extend the true histories of their nations far back into the mists of time—the further the better.

And yet, these histories—which have survived only in fragments quoted by later writers—still form part of the bedrock of the history and chronology of the ancient world. Manetho’s list of thirty or so Egyptian dynasties is the framework from which the whole chronology of the ancient world currently hangs.

Ptolemaic Reconstructions

The Ptolemies, however, were not content to merely rewrite the history of Egypt. They also tried to give currency to Manetho’s lies by rebuilding ancient monuments that had fallen into disrepair, by providing extant monuments with new inscriptions, and by building new monuments from scratch and attributing them to some long-dead Pharaoh or other. Or so I suspect.

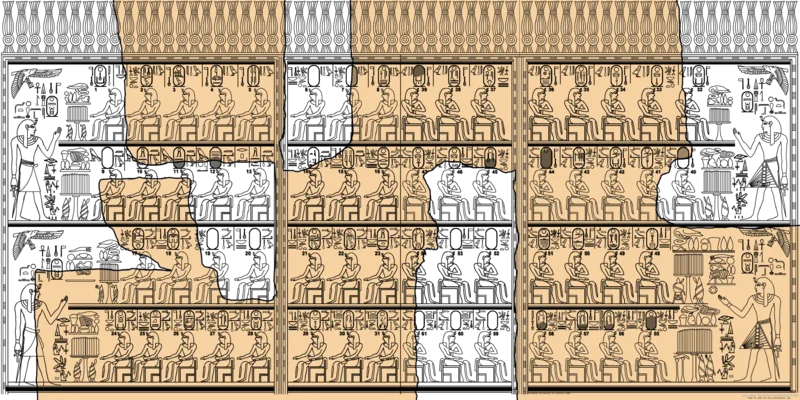

A case in point is the famous Karnak King List. This is a list of sixty-one pharaohs from the 4th dynasty to the 13th or 16th dynasty, inscribed in hieroglyphs on the wall of the Festival Hall of Thutmose III, a Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. I have no problem with the attribution of this building to Thutmose, but I believe that the King List was added by the Ptolemies—chisel in one hand, Manetho in the other—centuries after the death of Thutmose.

One of the proponents of the Short Chronology, Lynn E Rose, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of Buffalo, was perhaps the first to suggest that the Karnak King List is a Ptolemaic forgery. In 1992 Rose applied the techniques of astronomical retrocalculation to the El-Lahun Papyri and concluded that the Twelfth Dynasty had ruled over part of Egypt between 501 and 332 BCE, coming to an end in the year of Alexander the Great’s invasion. Not only was Rose relocating this dynasty about 1500 years closer to the present, he was also placing it after Thutmose III. How then could Thutmose’s scribe carve the names of Twelfth-Dynasty Pharaohs into the wall of his Festival Hall?

Even in the 19th century, the authenticity of the Karnak King List had been called into question. The Irish scholar Edward Hincks, best known for his contributions to the decipherment of Mesopotamian cuneiform, delivered a lecture to the Royal Irish Academy in 1842 in which he remarked:

I shewed, in the first place, that no reliance was to be placed on the collection of figures of kings, found in a chamber at Karnac, which had been assumed to be a genealogical tablet, similar to that of Abydos ... The so called “Tablet of Karnac” is, in fact, a mere collection of figures of kings, who had reigned, or were supposed to have reigned, in the various parts of Egypt, and perhaps in Ethiopia, placed together without any regard to order of succession. (Hincks 4)

Another adherent of the Short Chronology, Emmet Sweeney, is happy to accept the authenticity of the Karnak King List, as he believes that the Twelfth Dynasty was contemporaneous with Thutmose’s Eighteenth Dynasty:

To begin with, stratigraphy never shows any real distance between the Twelfth and Eighteenth Dynasties. On the contrary, they are consistently found at the same level. At Ugarit, for example, Claude Schaeffer found a Sphinx of Amenemhet III (Dynasty 12) next to alphabetic cuneiform tablets, which are known to date from the latter years of the 18th Dynasty ... This pattern repeats itself in all the excavated sites. Again and again archaeologists found material of the Twelfth Dynasty, along with that of the Eighteenth, immediately above that of the Hyksos. Where material of the two dynasties are actually found in the same buildings, or tombs, the Twelfth Dynasty material is normally explained away (as above) as “heirlooms”, a favorite method of disposing of uncomfortable anomalies.

The textual evidence agrees. The Karnak List of kings, compiled by Thutmose III, has the Old Kingdom (ending with Pepi II) followed by some of the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty, which in turn is followed by the Eighteenth (though the early kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty are missing). (Sweeney 109)

Lynn E. Rose was also skeptical about the credentials of the so-called Turin Canon:

I have some distaste for the expression “Turin Canon.” This is indeed the customary way of referring to the King-List that is written on the reverse side of the Turin Papyrus. But that King-List should probably not be considered all that “canonical”! That is why I prefer to call it the Turin King-List.

The Turin-King List gives us the names of a great many of those Thirteenth Dynasty kings. And this King-List itself seems to be from after the Thirteenth Dynasty. Most likely, then, the Turin King-List is Ptolemaic, since the Thirteenth Dynasty, whatever it may have been, seems likely to have extended at least a little beyond the death of Alexander the Great.

The Turin King-List may even be later than Manethon, rather than being one of his thousand-year-old sources, as is usually thought. But the Turin King-List has no dynastic numbers, just the Manethonian order for most of Dynasties One through Seventeen. (Ginenthal et al 609)

Would that the guardians of mainstream academia were as skeptical.

By the time of his death, Rose had even begun to suspect Herodotus—or, rather, his Alexandrian editors—of having tampered with history. His reconstructions of ancient chronology had led him to place the Egyptian rulers Apries and Amasis after Herodotus:

Yet both of them seem to have been already known to Herodotos in the late fifth century! The truth may be that the passages about Apries and Amasis were added long after Herodotos by Alexandrian editors, who edited practically everything, anyway. I once criticized Heinsohn for using such an argument in order to get himself out of difficulty. Having now found myself in a similar difficulty, I retract my criticism of Heinsohn. I hate it when that happens. While I am at it, I must retract my criticism of Rohl for speaking of “The New Chronology”, as if there were only one new chronology. I have in the meantime grown rather fond of speaking of “The Short Chronology”, even though the one that Ginenthal and I favor is but one of many such short chronologies. (Ginenthal 656)

Indeed. The Short Chronology is still a work in progress. Emmet Sweeney’s version, which I am currently leaning towards, identifies Apries and Amasis with men who lived and died before Herodotus visited Egypt.

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene was the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes. What Manetho did for Egypt, and Berossus for Chaldaea, Eratosthenes did for Greece. In his Timaeus (22b) Plato had written that the Greeks were mere children compared to the Egyptians, but Eratosthenes was too proud to accept this. It was he who declared that the fall of Troy occurred in 1183 BCE (Clement of Alexandria 1:21), a figure that is remarkably close to the one still found in textbooks today and which scholars insist is supported by radiocarbon dating. But where did Eratosthenes find this date?

Some centuries before Eratosthenes, Pythagoras preached the philosophy of metempsychosis: the transmigration of the soul, or, as we would call it today, reincarnation. His biographer Diogenes Laërtius recorded the following anecdote on the subject:

This is what Heraclides of Pontus tells us [Pythagoras] used to say about himself: that he had once been Aethalides and was accounted to be Hermes’ son, and Hermes told him he might choose any gift he liked except immortality; so he asked to retain through life and through death a memory of his experiences. Hence in life he could recall everything, and when he died he still kept the same memories. Afterwards in course of time his soul entered into Euphorbus and he was wounded by Menelaus. Now Euphorbus used to say that he had once been Aethalides and obtained this gift from Hermes, and then he told of the wanderings of his soul, how it migrated hither and thither, into how many plants and animals it had come, and all that it underwent in Hades, and all that the other souls there have to endure. When Euphorbus died, his soul passed into Hermotimus, and he also, wishing to authenticate the story, went up to the temple of Apollo at Branchidae, where he identified the shield which Menelaus, on his voyage home from Troy, had dedicated to Apollo, so he said: the shield being now so rotten through and through that the ivory facing only was left. When Hermotimus died, he became Pyrrhus, a fisherman of Delos, and again he remembered everything, how he was first Aethalides, then Euphorbus, then Hermotimus, and then Pyrrhus. But when Pyrrhus died, he became Pythagoras, and still remembered all the facts mentioned. (Diogenes Laertius 8:1:4)

Now, by general consent Pythagoras was born around 570 BCE. So when did Euphorbus die? Do the math. Between the death of Euphorbus and the birth of Pythagoras lay two complete lifetimes. Let us be generous and assume that both Pyrrhus and Hermotimus lived to be eighty. That would put the fall of Troy around 730 BC, almost half a millennium later than the date Eratosthenes assigned to this event.

Maybe Pythagoras, the Father of Mathematics, couldn’t add.

There are many other bits of evidence that prove that before the time of Eratosthenes the ancient Greeks recalled the Trojan War as a recent event:

Herakles is said to have sacked Troy a generation or so before the Trojan War. But he is also said to have inaugurated the Olympic Games in 776 BC.

Aeneus is reputed to have fled from the sack of Troy and to have founded Rome. The traditional date for the foundation of Rome is 754 BC. There is even good evidence that around 700 BC there was a major influx of settlers from Asia Minor into central Italy. Today we call these people the Etruscans. Were they refugees from the Trojan War?

On his way to Rome, Aeneus visited Dido, the founder of Carthage. Today, even mainstream academia places the founding of that city in the late 9th century.

It is obvious that Eratosthenes was a fabricator of history. He made shit up, and more than two thousand years later people are still buying it.

Critical Blinkers

So much of the past has been irrevocably lost. There are many things we would love to know about the ancient world but which neither we nor our successors will ever learn. That is just how it is. But this does not mean that we should let down our guard, or turn a blind eye to the evidence. We should always be suspicious when a gift horse shows up on our doorstep.

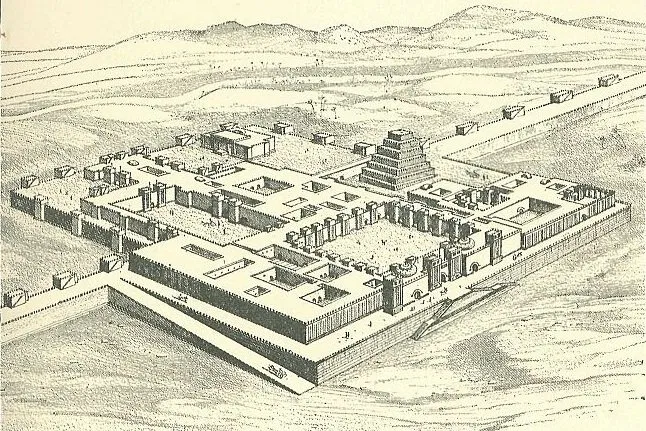

In the winter of 1932/33, archaeologists working for the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago discovered a list of Assyrian kings in the ruins of the ancient fortress city of Dur-Sharrukin (the modern Khorsabad). This Assyrian King List recorded the names of over one hundred rulers of the Assyrian Empire. (Two other King Lists have also been discovered—at the cities of Ashur and Nineveh—as well as two fragmentary lists.)

The archaeologists and Assyriologists could hardly contain their excitement. Here was a complete list of the kings who had ruled ancient Assyria from, it was thought, the latter half of the third millennium BCE to the middle of the 8th century (Frankfort 88). What a boon!

When the news of its discovery came to Chicago, Professor Breasted, then director of the Oriental Institute, charged the writer [Arno Poebel] with the publication of the list. Since the king list was one of the most outstanding finds of the Institute’s expeditions, it was Professor Breasted’s plan to have it published in an impressive form and with a full treatment of Assyrian chronology before 900 b.c, which it promised to place for the first time on a secure basis. (Poebel 247)

No one stopped to ask: Why would someone in the ancient world go to the time, trouble and expense of compiling such a list? It is naïve to think that some scholarly and scrupulously honest nerd made this for the benefit of posterity. The obvious answer is that the Assyrian King List, like all such king lists, was a piece of propaganda fabricated by a usurper in an attempt to justify his seizure of power:

Look, everybody, my father was the lawful king of Assyria for forty years, and his father was the lawful king before him, and his father before him, and so on. It is only right and just that I be the lawful ruler of Assyria today.

Every witness of history that has been handed down to us—whether of stone, clay, papyrus, or paper—should be treated as a suspect in an investigation. And that includes the Bible. Unquestioningly accepting the infallibility of Holy Scripture is not the way to get at the truth:

John Donne, Satire III, lines 79-81.

And Finally

I never did find out how Napoleon knew how old the pyramids were. Perhaps the Masons told him.

References

- William Adler, Paul Tuffin, The Chronography of George Synkellos: A Byzantine Chronicle of Universal History from the Creation, Translated with an Introduction and Notes, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2002)

- Eugène de Beauharnais, Memoires Et Correspondance Politique Et Militaire Du Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, Tome Premier, Michel Lévy Frères, Paris (1858)

- Clement of Alexandria, Stromata [Miscellanies], in Alexander Roberts & James Donaldson (editors), Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume 4, T and T Clark, Edinburgh (1867)

- John Donne, Poems of John Donne, Volume II, Edited by E K Chambers, A H Bullen, London (1901)

- Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Volume 2, Translated by Robert Drew Hicks, Loeb Classical Library L184, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1925)

- Henri Frankfort, Iraq Excavations of the Oriental Institute 1932/33, Third Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1934)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 4, Ivy Press Books, Forest Hills NY (2012)

- Charles Ginenthal, Irving Wolfe, Lynn E. Rose, Dwardu Cardona, David N. Talbott, Ev Cochrane, Stephen J. Gould and Immanuel Velikovsky: Essays in the Continuing Velikovsky Affair, Dale Ann Pearlman (editor) (1996-2013)

- Edward Hincks, On the Age of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Manetho, Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 21, Polite Literature, pp 3-10, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1846)

- Plato, Timaeus, in Benjamin Jowett, The Dialogues of Plato, Translated into English with Analyses and Introductions, Volume 3, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1892)

- Arno Poebel, The Assyrian King List from Khorsabad, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Volume 1, Number 3 (July 1942), pp 247-306, Volume 1, Number 4 (October 1942), pp 460-492, Volume 2, Number 1 (January 1943), pp 56-90, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1942)

- Claude Schaeffer, Stratigraphie Comparée et Chronologie de l’Asie Occidentale, Oxford University Press, London (1948)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Pyramid Age, Ages in Alignment, Volume 2, Algora Publishing, New York (2007)

- James Ussher, Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti, una cum rerum Asiaticarum et Aegyptiacarum chronico, a temporis historici principio usque ad Maccabaicorum initia producto [Annals of the Old Testament, Deduced from the First Origins of the World to the Beginning of the Maccabees, Together with a Chronicle of Asiatic and Egyptian Matters], and Annalium pars posterior [The Latter Part of the Annals, F Crook & G Beddell, London (1650, 1654)

- James Ussher, Larry and Marion Pierce (editors), The Annals of the World, Revised and Updated from the 1658 English Translation, Master Books, Green Forest, AR (2003)

- W G Waddell (translator & editor, Manetho, Loeb Classical Library L350, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1964)

Image Credits

- The Great Isaiah Scroll of Qumran: © Israel Museum, Fair Use

- Immanuel Velikovsky: Wikimedia Commons, Donna Foster Roizen (photographer), © Frederic Jueneman, Creative Commons License

- The Battle of the Pyramids: Wikimedia Commons, Louis-François Baron Lejeune (painter), Public Domain

- James Ussher: Wikimedia Commons, National Portrait Gallery, London, Peter Lely (painter), Public Domain

- The Annals of the World: © Larry and Marion Pierce, Fair Use

- The Scribe: The Cooper Gallery, George Cattermole (painter), Fair Use

- Ptolemy II: Wikimedia Commons, © 2011 Marie-Lan Nguyen, Creative Commons License

- Antiochus I: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons License

- A Modern Drawing of the Karnak King List: Wikimedia Commons, © PLstrom, Creative Commons License

- Lynn E Rose: The Velikovsky Encyclopedia, Fair Use

- Eratosthenes: Wikimedia Commons, Philipp Daniel Lippert, Dactyliothec, Public Domain

- Sargon’s Palace at Dur-Sharrukin: Boudier (artist), Felix Thomas (restoration artist), Public Domain