The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Mesopotamia before the conquests of Alexander the Great:

| Dates BCE | Upper Mesopotamia | Lower Mesopotamia |

|---|---|---|

| 540-330 | Persian Empire | Persian Empire |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes | Second Chaldaeans |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire | Assyrian Empire and Scythians |

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians | First Chaldaeans |

In this article we will examine Part 6 of Heinsohn’s lecture: The Restoration of Ancient Israel by Abandoning Fundamentalist Dates of Historical Biblical Narratives as well as Pseudo-Scholarly Dates of Strata in The Land Of Israel. In this section, Heinsohn reconstructs the chronology of Ancient Israel, which requires a drastic shortening of the historical timeline:

Mainstream scholars are in the process of deleting Ancient Israel from history books. The entire period from Abraham the Patriarch in the -21st century (fundamentalist date) to the flowering of the Divided Kingdom in the -9th century (fundamentalist date) is found missing in the archaeological record. The period from the -9th to the -6th century (fundamentalist dates) is bewildering, for a different reason. The corresponding strata are found immediately below Hellenism of -300. Moreover, there are no windblown layers between Hellenistic strata of -300 and Israel/Judah strata of 700/-600, and the material culture (architecture, artifacts, ceramics etc. ) between -600 and -300 is clearly continuous. From an unbiased stratigraphical point of view, therefore, what now is fundamentalistically dated -900 to -600 requires a hard evidence chronology of -600 to -300. Yet, if the strata now dated -900 to -600 in biblical years are changed to -600 to -300 in evidence based years, Israel’s entire biblical history from -2100 to -600 is lost. Statements like “historical Israel remained as elusive as ever”, therefore, dominate the most ‛advanced’ level of Bible research (T. L. Thompson, Early History of the Israelite People, Leiden, 1992, p. 26). (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn begins his reconstruction of Israelite Chronology by locating the Exodus at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, when the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt. I agree with this relative date, but in absolute terms I follow Charles Ginenthal and Lynn E Rose, who hypothesized that the absolute date of Exodus was around 763 BCE. This is more than a century earlier than the radical solution proposed by Heinsohn:

The Exodus provides a typical example for the mismatch between the biblical date of a biblical historical event, and the mainstream date for a stratum in Israel. A stratum which would fit the story does exist. Yet, the story is discarded because the stratum in question has received an unfitting date. If, however, both unscholarly dates are discarded, the Exodus might well reenter history books. I put the “Exodus” event at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, when the Hyksos are expelled from Egypt. To the writer, this expulsion is identical with the expulsion of the pre-Medish Ninos-Assyrians from Egypt. Therefore, the Exodus falls in the time of the rise of Media, i.e., in conventional terms, of the Mitanni. The Medes = Mitanni emerge as the new superpower around -630. An Exodus date of ca. -630, of course, has nothing to do with a biblical Exodus date of -1450 or with a mainstream Hyksos expulsion date of ca. -1550. The latter pseudo-astronomical Sothic date of -1550 led to the discarding of the Exodus story because it came too late. (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn finds support for his relative dating of the Exodus and subsequent Conquest of Canaan in the writings of the Israeli archaeologist Amihai Mazar, whose Archaeology of the Land of the Bible has become a standard textbook for the history and archaeology of Canaan. In this book, Mazar summarizes the situation in Canaan at the end of the Middle Bronze Age:

The most significant event concerning Palestine was the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt in the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. The Hyksos princes fled from the eastern Delta of Egypt to southern Palestine; the Egyptians followed them there and put them under siege in the city of Sharuhen. This event was probably followed by turmoil and military conflicts throughout the country, as a significant number of Middle Bronze cities were destroyed during the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. These destructions caused a collapse in entire urban clusters in the country. Thus, in the south, cities along Beersheba and Besor brooks were destroyed, and they hardly continued to exist in the following period ... In the coastal plain and the Shephelah, Tell Beit Mirsim, Gezer, Tel Batash and Aphek suffered from destructions and severe changes in their occupation history. In the northern coastal plain, the large city at Kabri was abandoned. In the central hill region and the Jordan Valley, a chain of Middle Bronze cities and villages came to an end, and only few revived in the following period. Examples are Jericho,Hebron, Beth-Zur, Jerusalem, and Shiloh.

However, unlike the great collapse of the urban culture at the end of the EB III period, the turmoils in the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. did not cause a total break of the Canaanite urban culture. Important cities in the northern part of the country, such as Hazor and Megiddo, suffered some disturbance at this period but soon were rebuilt on the same outline. Major temples at these cities were rehabilitated and continued to be in use in the Late Bronze period. The cultural continuity can be seen also in terms of pottery production, crafts, and art. Thus, the wide-scale destructions in the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. which mark the end of the Middle Bronze Age, did not bring an end to the Canaanite civilization. (Mazar 226 ... 227)

By adopting the approximate date of 630 BCE for the Exodus, Heinsohn has left himself about 700 years in which to fit the entire history of the Israelites from the Exodus to the destruction of the Second Temple by the future Roman Emperor Titus, which even he dates to 70 CE. This necessitates a drastic contraction of the timeline:

By taking stratigraphy seriously, I also had to restore the Amarna correspondence to its evidence-based chronological position. The partners of the Medes (“Mitanni”) in Akhet-Aten are to be dated to the late -7th and early -6th century of the Medes. The founder of the “House of David” emerged in these turmoils from a tribal background in the Judaean territory. The biblical narratives about David put him nearly half a millennium after Joshua and Exodus. Yet, all the ingredients of the stories indicate their contemporaneity. The compilers of the Bible put 500 years between them, because they did not know better. They had no resort to libraries, and were in no position to check the dates and sequences of events by looking at the stratigraphy. (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn believes that the Joshuan Conquest was finally halted by the Medes in northern Canaan, whom he identifies with the Bible’s Amorites. He also suggests that the Amalekites of the Bible were not Arabs but Scythians—the former allies of the Assyrians/Hyksos, who rebelled and initially sided with the Medes in bringing down the Assyrian Empire. Subsequently, however, the Scythians turned on the Medes. Herodotus records that the Scythians were the dominant power in the Ancient East for twenty-eight years. During this time, they had designs on Egypt but were thwarted by the Pharaoh Psammetichus (Godley 133-137, The Histories 1:103-106).

Heinsohn, therefore, makes Joshua and David contemporaries. Joshua carved out the Kingdom of Israel in northern Canaan with the Israelites who had taken part in the Exodus. David created the Kingdom of Judah in the south with the Judahites, who had remained in Canaan. In his earlier book Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Heinsohn suggested that David and Solomon were local princes who had been conflated by the authors of the Bible with mythical astral-deities and with the “Neo-Assyrian” Emperors Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmaneser III (Heinsohn 1988:250):

From this context it becomes clear that early Judah and early Israel, simultaneously, lived under Egyptian and/or Medish rule during the -7th/-6th century. The steady growth of these ethno-political entities in the early -6th century could not have gone unnoticed by these big powers. And, indeed, the Amarna correspondence of the early -6th Medes=Mitanni mentions warring and conquering Habiru time and time again. These statements, I conclude, refer to further conquests of the “Exodus”-people and to the expansion of the House of David. (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn is not the first to suggest that the Habiru mentioned in the Amarna Letters and elsewhere are Hebrews, though this identification has been contested by many scholars. Even Immanuel Velikovsky, the Father of the Short Chronology, rejected the Habiru-Hebrews equation (Velikovsky 225-229).

Tel Dan

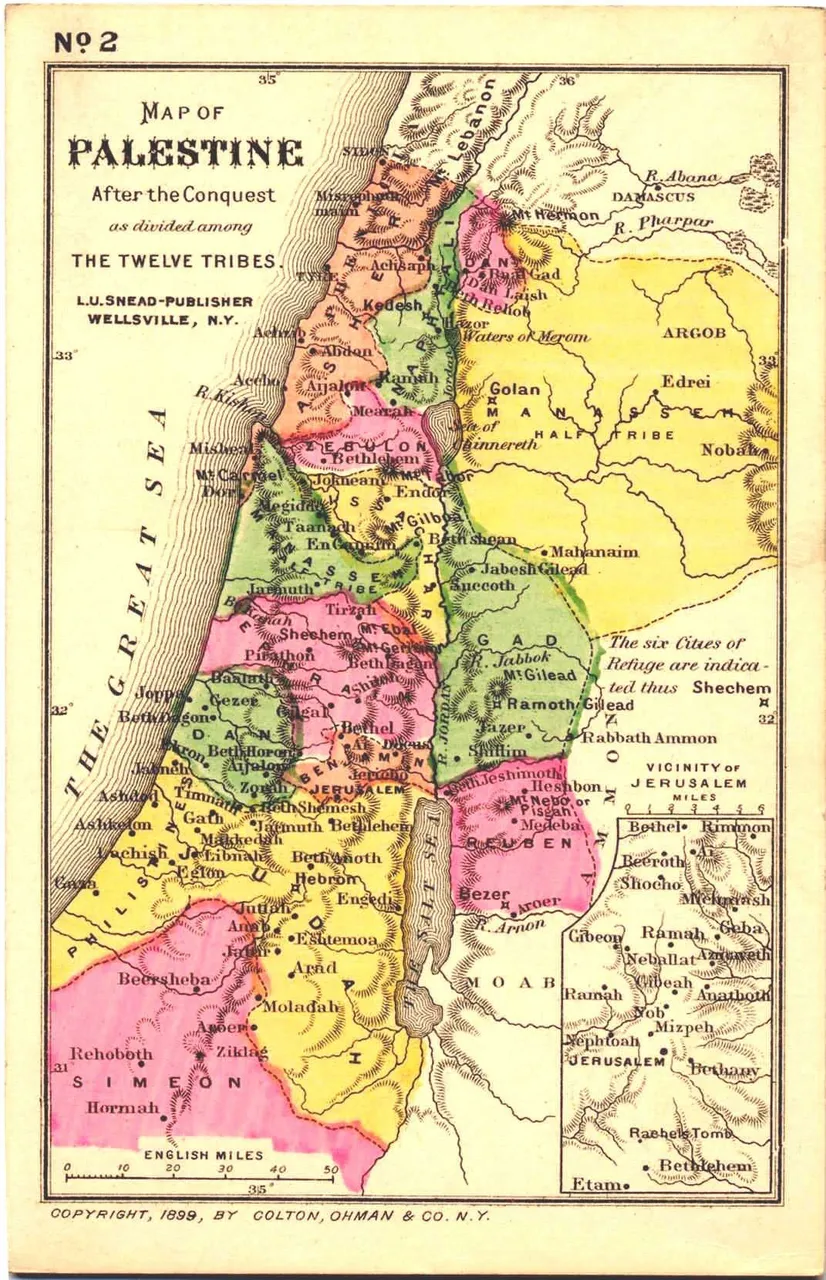

The stratigraphic evidence that Heinsohn adduces in support of his model of the Short Chronology comes from the archaeological site of Tel Dan (Tell el-Qadi) at the foot of Mount Hermon, where the ruins of Dan, the northernmost city of Ancient Israel, lie. The original name of the city was Laish, and it is under that name that it is sometimes mentioned in the Bible (eg Joshua 19:47, Judges 18:29). It was renamed after the Israelite Tribe of Dan, in whose territory it stood.

Now, with the House of David emerging in the Medish period we should be able to look for descendants of this princely house in the Persian period, which immediately follows Media, around -540. To do this, one has to scan the strata found immediately below the Hellenistic strata, which are dated beginning around -300. If one performs such a search program in Tel Dan, he or she will have to start immediately below its Hellenistic stratum I. Abraham Biran found his stele, with the “House of David” inscription, in a location belonging somewhere between Dan’s strata II and III. That is as close to a Persian period successor of David as one can get. It also confirms the identity of Shalmaneser III—Jehu’s overlord [cf. Part III above]—who had to be identified with early -5th century Artaxerxes I in the garb of his Assyrian satrapy. (Heinsohn)

Heinsohn identified the “Neo-Assyrian” Emperor Shalmaneser III with the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes I in an earlier part of his talk: Stratigraphical Puzzles of the Persian Empire. Emmet Sweeney, one of Heinsohn’s disciples, identifies Shalmaneser III with the Median Emperor Cyaxares II and Esarhaddon with Artaxerxes I (Sweeney 16).

The Tel Dan Stele referred to above was discovered at Tel Dan in 1993 by a member of the archaeological team lead by Avraham Biran. The fragmentary text of this stone is written in alphabetic Aramaic and mentions the House of David, Jehoram King of Israel, and Ahaziah son of Jehoram. The authenticity of the stele has been questioned and the translation disputed, but both are now widely accepted.

Tel Dan has been extensively excavated. In 1963, a short exploratory excavation was carried out by Z Yelvin before Avraham Biran of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums (and later Director of the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology) embarked upon a remarkable series of excavations spanning thirty-three years (1966-1999).

The earliest remains discovered so far at Tel Dan belong to the Early Bronze Age II ... Evidence for a Middle Bronze Age II-A occupation also was found. During the Middle Bronze Age II-B the city was strongly fortified with huge ramparts ... Tel Dan continued to enjoy prosperity during the Middle Bronze Age II-C and Late Bronze Age. The people of that time, as well as those of the Iron Age I, lived within the enclosure and safety of the earthen ramparts. (Avi-Yonah & Stern 1:321)

Neolithic pottery has also been found beneath the oldest dwellings. In the following diagram, Heinsohn’s interpretation of Tel Dan’s stratigraphy is compared with the conventional interpretation:

| Stratum | Period | Conventional | Heinsohn |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | Late Mameluke, Early Ottoman | 1400-1600 CE | - |

| - | Late Roman | 100-400 CE | - |

| - | Hellenistic | 300-200 BCE | 300-200 BCE |

| I | Iron IIC | 700-600 | -300 |

| II | Iron IIB | 750-700 | - |

| IIIA | Iron IIB | 800-750 | - |

| IIIB | Iron IIB | 850-800 | 425- |

| IVA | Iron IIA | 900-850 | -425 |

| IVB | Iron IB | 1000-900 | 480- |

| V | Iron IA | 1100-1000 | -480 |

| VI | Iron IA | 1200-1100 | 540- |

| VIIA | Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 | -540 |

| VIIB | Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 | - |

| VIII | Late Bronze I | 1500-1400 | 630- |

| IX | Middle Bronze III | 1600-1500 | -630 |

| X | Middle Bronze II | 1700-1600 | - |

| XI | Middle Bronze II | 1800-1700 | 750- |

| XII | Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 | -750 |

| XIII | Intermediate Bronze | 2300-2000 | 800- |

| XIV | Early Bronze III | 2700-2300 | -800 |

| XV | Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 | - |

| XVI | Neolithic | 5000 | - |

(Source: Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology)

Heinsohn rejects the three-to-four-century-long gap between the Iron Age and the Hellenistic Period. This hiatus, or occupation gap, is required by the conventional chronology. According to Biran, the Iron Age at Dan came to end sometime after 750 BCE when the entire site was destroyed in a great conflagration. The cause of this destruction is unknown. Biran suggested that the “Neo-Assyrian” Emperor Tiglath Pileser III was the culprit, but there is no record of any such event in either his annals or the Bible. He did subdue the Kingdom of Israel, as recorded in Annal 18 of the Kalḫu Annals. Unfortunately, this text is fragmentary. The deportation of thousands of captives is recorded, and although some cities are named, there is no mention of the burning of Dan:

I en[veloped] him [like] a (dense) fog [... I] utterly demolished ... of sixteen districts of the land Bīt Ḫum[ria (Israel). I carried off (to Assyria) ... captives from the city ...]barâ, 625 captives from the city ...a[..., ... (5´) ... captives from the city] Ḫinatuna, 650 captives from the city Ku[..., ... captives from the city Ya]ṭbite, 656 from the city Sa...[..., ..., with their belongings. I ...] the cities Arumâ (and) Marum [...]. (Tadmor & Yamada 62-63, Luckenbill 279-280)

There are eight principal strata between the end of the Middle Bronze Age (which Heinsohn dates to about 630 BCE) and the beginning of the Hellenistic Period (around 330 BCE). This means that, on average, each stratum must have accumulated in only about 12-13 years. In the conventional chronology, at least fifty years are allowed for each stratum. It is impossible to know how much time is required for a given stratum to accumulate. It only takes months to build houses, strongholds and city walls. And it only takes minutes for them to be levelled by the hand of nature or of man. It is the rubble of such a levelling that creates a new stratum.

The very fact that so many ancient archaeological cities are stratified testifies to periodic catastrophes—whether man-made or natural. Each stratum represents a settlement that was razed by some catastrophic event. The survivors then levelled the site and rebuilt the city, creating a new stratum. Without further knowledge, one can only guess how much time elapsed between successive strata.

The Devil and the Details

Heinsohn does not provide a detailed chronology of the history of Ancient Israel—one, for example, which includes the accession dates of the various Kings of Israel and Judah. He merely sketches out the timeline. Using this sketch, however, a more detailed timeline may be reconstructed:

| Dates BCE | Period | Israelites |

|---|---|---|

| 330-140 | Hellenistic | Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire |

| 530-330 | Persians | Kingdoms of Israel and Judah |

| 620-530 | Medes (Amorites) and Hittites in Canaan | Joshuan and Davidic Habiru |

| 720-620 | Hyksos | Judahites in Canaan and Israelites in Egypt |

| 800-720 | Patriarchal Era | Abrahamic Semites |

| 950-800 | Pre-Semitic Canaanites | (Semites in Chaldaea) |

Israel: A Heinsohnian Timeline

950: Pre-Semitic Canaanites establish Canaan’s first urban civilization

800: Abraham (Semitic) migrates from Chaldaea and settles in Canaan.

720: The Hyksos (Assyrians) conquer Canaan and Egypt.

700: The House of Israel settles in Egypt. Other Abrahamic Semites, the ancestors of the Judahites, remain in Canaan.

630: The Medes (Mitanni) invade Mesopotamia and attack the Assyrian Empire with the assistance of Assyria’s former allies, the Scythians, and the Hittites (Cappadocians).

620: The Hyksos are expelled from Egypt. The Exodus of the Israelites takes place and they return to Canaan.

620: The Medes (Amorites) and the Hittites conquer Canaan. Joshua and David lay the foundations of the future Kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

530: The Persians conquer Canaan and set up the Satrapy of Eber-Nari (or Transeuphratia). The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah are initially permitted to exist subject to the Satrap. Israel, however, asserts its independence and is destroyed. Judah is destroyed sometime later and the Judaeans are carried off into Babylonian Captivity.

332: The Macedonian Conquest of Canaan by Alexander the Great.

I have not been able to confirm when, according to Heinsohn, the Kingdom of Judah was destroyed and the Judaeans were deported to Babylon. Were the Persians responsible for this? Was it Alexander the Great who ended the Babylonian Captivity? In the conventional timeline, it was Cyrus the Great who freed the Judaeans.

Heinsohn’s Canaanite model of the Short Chronology is quite different from both the model devised by Charles Ginenthal & Lynn E Rose and the one devised by Emmet Sweeney. Heinsohn’s timeline is even more compressed than theirs. It is difficult to see how the reigns of the Kings of Israel and Judah are meant to fit into this scheme. In the conventional chronology, for example, the Kingdom of Israel lasted for about two centuries, from 930-720 BCE, while the Kingdom of Judah endured for over three hundred years, from 930-586 BCE. Several pertinent questions arise:

Does Heinsohn accept these figures as accurate approximations of the durations of these kingdoms?

When exactly did the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah arise? Around 630-620 BCE, where he places Joshua and David? Or around 530 BCE, when the Persian Satrapy of Eber-Nari (Transeuphratia) was created?

When did the Kingdom of Israel fall? When did the Kingdom of Judah fall?

Who or what brought the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah to an end? The Persians? The Macedonians?

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Michael Avi-Yonah, Ephraim Stern (editors), The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, Prentice-Hall Incorporated, Englewood Cliffs, NJ (1975)

- Ian Barnes, The Historical Atlas of the Bible, Quantum Publishing, London (2014)

- Alfred Denis Godley (translator), Herodotus, Volume 1, The Histories, Books 1-2, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1920)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Bablyonia, Volume 1, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1926)

- Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 10,000–586 B.C.E., Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday, New York (1990)

- Emmet Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes, and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Hayim Tadmor & Shigeo Yamada, The Royal Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III, King of Assyria (744-727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726-722 BC), Kings of Assyria, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN (2011)

- Thomas L Thompson, Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written and Archaeological Sources, E J Brill, Leiden (1992)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Ages in Chaos, Volume 1, From the Exodus to King Akhnaton, Doubleday & Company, Inc, Garden City, NY (1952)

Image Credits

- The Conquest of Canaan: © Quantum Publishing, Cartographica Press (cartographers), Ian Barnes (author), The Historical Atlas of the Bible, Page 105, Quantum Publishing, London (2014), Fair Use

- Map of Canaan after Joshua’s Conquest: Colton, Ohman & Co, New York, Public Domain

- Amihai Mazar: © Arielinson, Creative Commons License

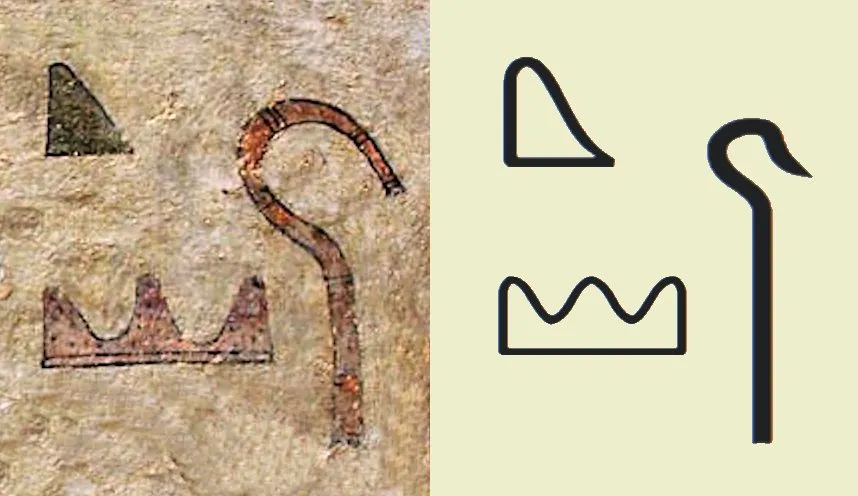

- Hieroglyphs for Hyksos: Tomb BH3 of Khnumhotep II, Beni Hasan, Egypt, Public Domain

- Tiglath-Pileser III: Stela, British Museum, Public Domain

- Shalmaneser III: Kurba’il Statue of Shalmaneser III from Fort Shalmaneser (Nimrud, Iraq), Iraq Museum, ND10000, © Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Canaanite Gate at Tel Dan (Middle Bronze Age): © DinaKuzia (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Tel Dan Stele: Israel Musuem, Jerusalem, © Gary Todd (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Avraham Biran: © The Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology, Fair Use

- Tel Dan: © Madain Project 2017 - 2021, Fair Use

Online Resources