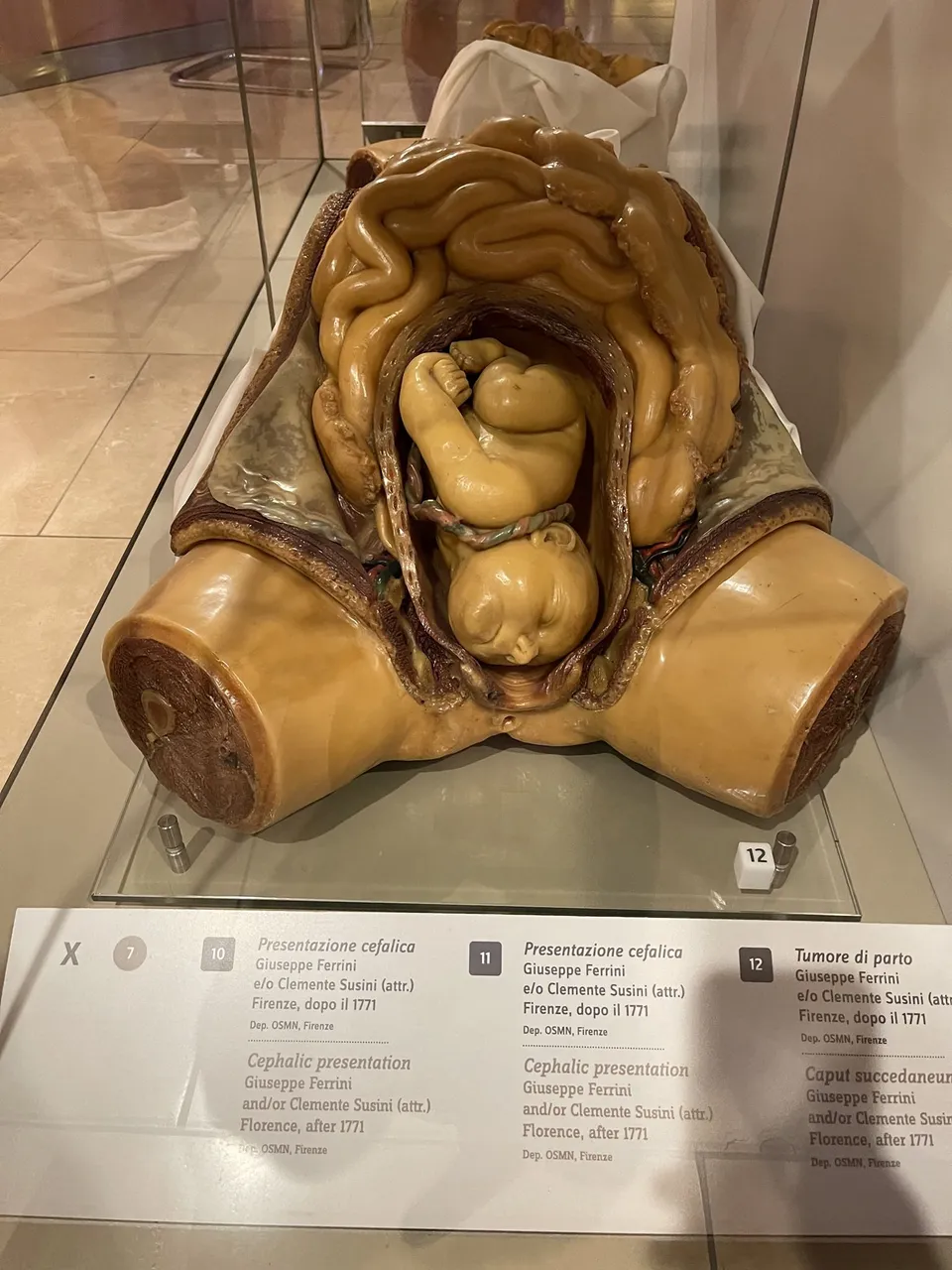

One of the most emotionally powerful exhibits from the Galileo Museum in Florence was a set of wax sculptures from the late 1700s depicting the various ways a birth could fail.

It's hard to overstate how big the problem was at the time -- every time a woman gave birth in that era, she had a 1 in 7 chance of losing her baby in the first year, and she had a 1 in 100 chance of dying during childbirth. Given that women at the time had an average of 7 children in some parts of Europe, that added up to a 1 in 14 chance of the mother dying in childbirth before her childbearing years were over. This means everyone knew many women who had died in childbirth, usually at a young age.

It didn't matter if you were the queen and had the best medical care in the world. Those were the odds.

So scientists worked incredibly hard to understand the problem, dissecting cadavers, taking extensive notes on different types of breech births, and developing forceps to help reorient the baby. They also developed techniques that could save the mother's life by killing the baby, or could save the baby but likely kill the mother. Painfully, they were still another century away from the germ theory of disease, the knowledge of antiseptics, and the use of anesthesia for surgery. It would take another half-century after that before C-sections started to be reasonably safe.

They clearly understood the problem in great detail in the 1700s, but they had no way of solving it, and it was killing many of their loved ones.