Enter Kristen Grauer-Gray – our tireless leader. For half-a-decade she trained Liberian teachers on how to bring classrooms to life using local, affordable materials. She wrote the 132-page "Hands-on Liberia" Lab Manual – a de facto Bible of science.

She trained countless teachers, then took it one step further and trained fellow volunteers to train teachers. She once crushed an industrial fuel barrel using atmospheric pressure – very nice! Collaborating with the Ministry of Education, she and others nucleated a new volunteer assignment; Science Lab organizer and instructor.

Our mission was to revitalize hands-on learning in schools that already had established science laboratories. Most county capitals were fortunate enough to have well-stocked labs, primarily built and stocked through an NGO project in the mid-2000s. They looked nice, and even on paper they are impressive. To me, however, they reflect a major failure of foreign-aid initiatives in the region.

Money flows to the what and not the who. What do schools need and what can we give them instead of whose capacity do we build such that the schools can provide for themselves. Give a man a fish or teach him to fish? Many of these high-end labs became dusty vessels ripe for the looting.

With care, practical know-how, and re-bar-inforcement, these labs could foster intrigue among students who otherwise spent the day in front of one chalkboard. Thomas Varmah, the Chemistry teacher at Bopolu Central High School, recognized this. When I arrived in early September, he surprised me with labeled dilute acids and bases and stories of what worked in years past. Right then I knew he’d be the perfect co-instructor.

Together we bounced from school to school handing out letters and inviting science teachers to attend our Saturday teacher training. We sent out frequency-modulated radio waves at 90.7 Megahertz to recruit educators in surrounding towns (sounds approximately 19-times cooler than “advertised on the radio”). Starting that weekend, the 7-week course covered topics from unit conversion to parallel circuits.

Our primary goal was to answer schools’ plea’s for guidance on how to teach the “Practical” sections of the West African Secondary School Certificate Examination (WASSCE). This comprehensive test – for which a pass is technically required to graduate high-school in Liberia – expects students to master the use of scientific apparatuses like pipettes and binocular compound microscopes. With only occasional exposure to chalkboard drawings of the sort, this is “practically” impossible.

Our secondary goal – which really acted as a vehicle for the first – was to enable science teachers to make their labs localized, interactive, and replicable. Varmah and I were impressed by the commitment of certain teachers, like Mulbah Massaquio, who showed up early each and every Saturday. At the same time, we were disappointed that others preferred to hit the Palm Wine station early on their days off. Understandable, seeing as many taught at two schools on weekdays just to put rice in the pot.

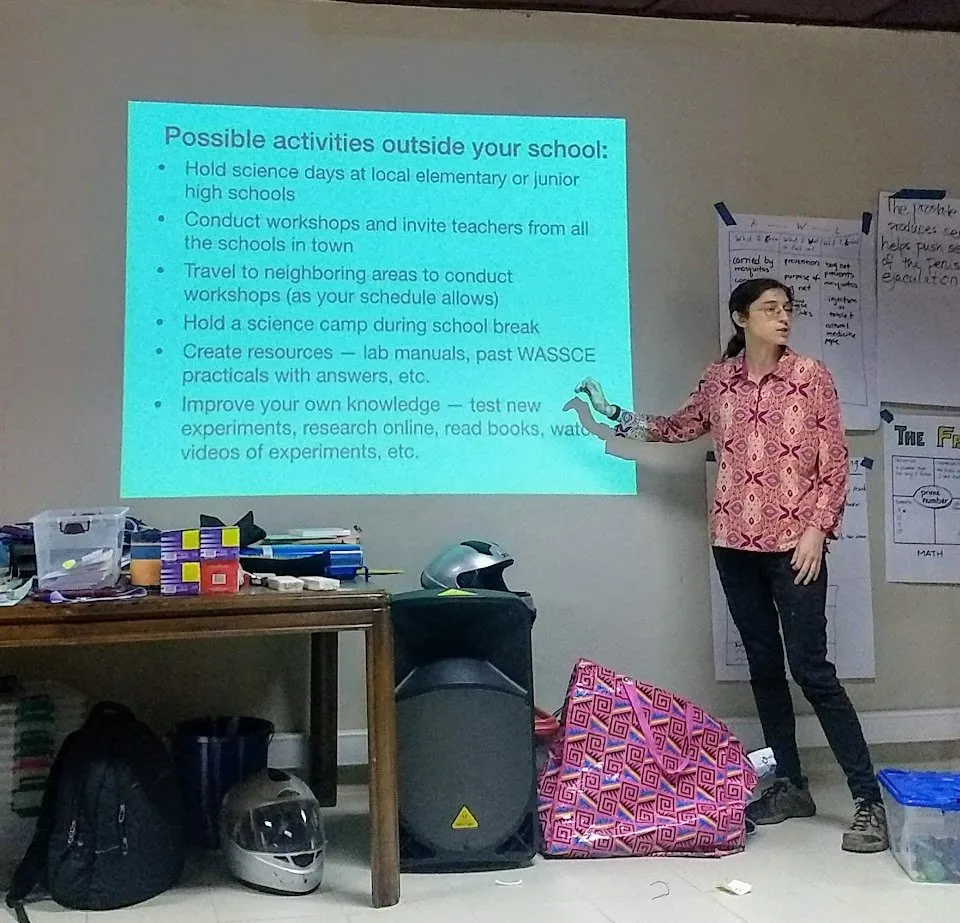

A sample of another Saturday session’s objective is seen here:

Participants will measure the extension of springs with varied applied forces to determine the spring constant using Hooke's law. Successful participants will use coordinate graphing to aid in their discovery. Participants will then observe locally collected plant samples to differentiate between monocotyledons and dicotyledons, then draw a specimen using the WASSCE drawing format.

The final Saturday was the participant's first chance to apply what they practiced. In groups of two they designed and presented lessons on familiar lab experiments to school principals, the county education officer, and a reporter from the Voice of Bopolu frequency-modulating station. We checked in with the trained teachers, observing what portions or ideas they carried back to their classrooms. Young teachers showed the most immediate changes in their style and use of teaching aids. It’s hard to know if any lasting impact was made without periodic monitoring. This is one of the more frustrating facets of Peace Corps service – to plant trees under whose shade we may never sit.

Another dedicated group of learners were those in our STEM Club. We met weekly to run experiments, collect atmospheric measurements, and engineer with Legos. In Liberia, every organization must have a motto. And the motto must start with “Motto:”. Ours was the brainchild of the precocious Ezekiel T. Doe; “Motto: Our future is in our Hands”. Most of the time it was dirt or plastic bricks in his hands, but we got the idea.

Working with the NASA GLOBE program, the STEM club students measured temperature, barometric pressure, and precipitation, uploading the data on GLOBE web interface. Their favorite, perhaps a universal favorite, was Legos. Whether building the tallest wind-resistant tower or strongest load-bearing bridge, their ears were split by smiles.