He has been here for three weeks, every day. And things have gotten better, he says, much better. Horst L., who has spent a lifetime working as a long-distance cable fitter, looks back with satisfaction on what he himself calls "his crazy Corona time." Four weeks in the balloon, he says, every night in a sleeping bag, initially still outside in the bushes at the parking lot in front of the large vaccination center in Bautzen, Saxony (name changed), where secret deliveries of the precious vaccine from Moderna and Biontech arrive daily, meticulously screened and inconspicuous.

The man who can wait

L., still a handsome man of 82, taut posture, slim glasses, dark parka and sturdy boots on his feet, has lived here ever since he made a decision to change his life, but above all to save it. "I got tired of it after the 270th try," he says of his attempts to get a vaccination appointment through the federal vaccination hotline or Internet address. "It just wasn't working."

A conversation at the bakery then made the trained telecommunications mechanic of the former German postal service take notice. "An older lady my age told me that she felt the same way." But then she looked out of the window one evening and saw that there was not a single car with people wanting to be vaccinated parked in front of the brightly lit vaccination center. Spontaneously and without much of a plan, she and her husband simply strolled over there, that was before the big snow and there was no curfew.

Always a panic about leftovers

It turned out to be a great idea," reports Horst L., "because there was a lot of panic in the vaccination center. Shortly before closing time, there were still seven syringes lying around, but there was a lack of people willing to be vaccinated. Fortunately, the security guard at the gate had just heard that. "He waved the woman and and her husband right through, and half an hour later they were both immunized."

Horst L. based his personal plan for survival in the Corona crisis on this small experience. "I thought to myself, if I'm on the spot, if once again a vaccination residue has accumulated, then they'll give it to me already, they're not brutes." But since he himself lives in a village several kilometers away from the vaccination center, which radiates far into the region on snowy nights, he decided to move there. "I used to be in the Army," he says, "I certainly don't mind spending the night outside."

Two layers of underwear

So in mid-January, the spry senior moved. Armed with two layers of underwear, a small tent, a crate of small "Jägermeister" bottles "against the cold" (L.) and a thick down sleeping bag, he set up camp in the bushes in front of the IZ, facing the entrance gate. "So I can see what's going on there at any time." L. brought a gas stove, enough food for three days at a time. In between, he had decided, he would always go home to take a shower.

There is usually nothing going on in the IZ because it is closed for lack of vaccine. At the beginning, he was very disappointed with the start of the largest vaccination campaign in history, Horst L. admits. "I could see vaccination week after vaccination week that it was hardly making any progress." The leftover vaccine he had speculated on was scarce to begin with because there was little vaccine overall. "The little that was left over was then, of course, immediately given to local officials who are particularly vulnerable because of their work on the disaster staff," the vaccine hunter says insightfully.

Holding out until the spike

Still, he says, he was determined not to give up until he received his prick. Then, when the big snow came, help arrived. By now, L. had made friends with several of the immunization center's protective guard staff, and he was no longer a stranger to the facility's nurses, orderlies and doctors, cleaners and list keepers. "People know each other, now and then someone from the IZ even brings me a coffee or a tea." Of course, imemr with distance, always wearing a mask. "We're all professionals here."

Accordingly, people at the IZ were probably worried when the temperatures plummeted on the first night of the snow disaster. Horst L. smiles, today he confesses that he did not spend that night in the tent, but with an acquaintance "around the corner". But in the morning he was back on the spot, just in time to be invited by the head of the IZ to hope for his vaccination in the facility in the future. "We have room," the professor ordered me, but at the same time he made it clear that I should not believe that my moving in would immediately leave an extra box."

His own little corner in the waiting room

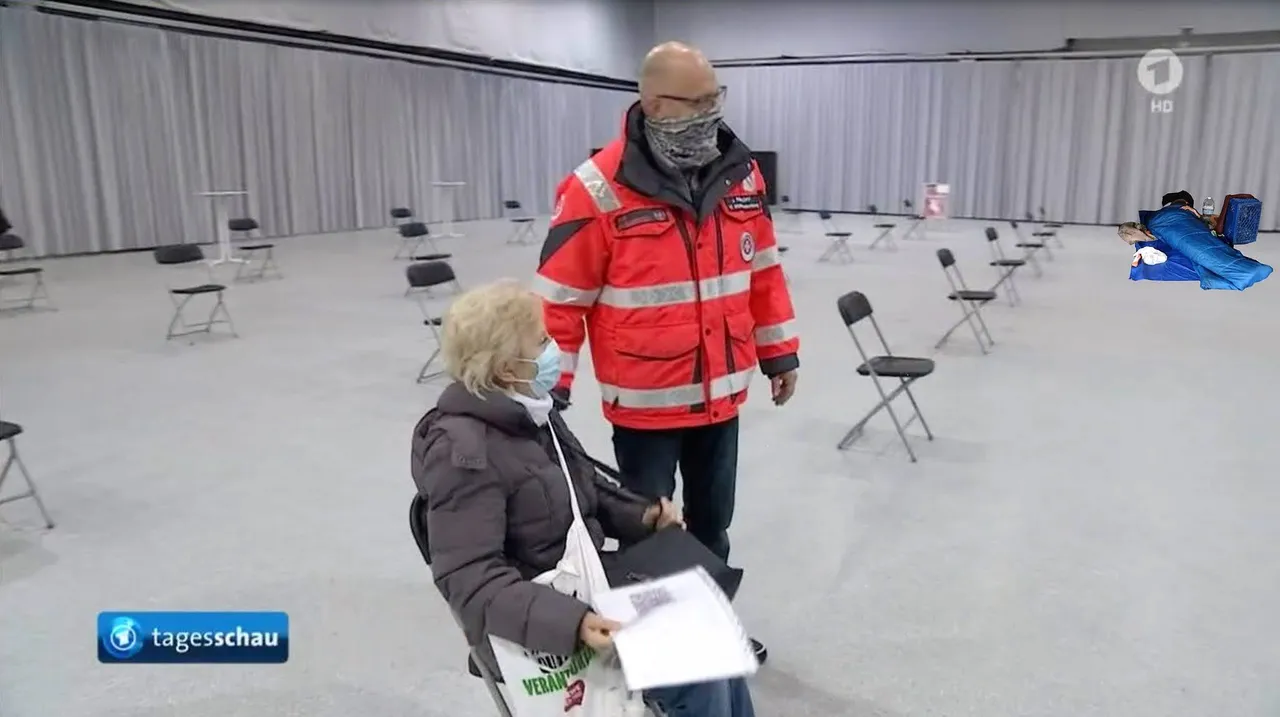

After almost five weeks in the IZ, no one knows this better than Horst L. Every day he waits, as quiet as a mouse, snuggled into a sleeping bag at the very end of the large waiting and separation area of the IZ, which is designed for 12,000 people, but is currently only used by about 17 a day. Every now and then it looked as if a syringe would be left over, he describes, but IZ staff always managed to reach a high-risk patient from Group 1, which includes over-80s, nursing staff, doctors and selected administrative staff.

That's a shame for me, but I'm not losing heart," says L. He's sure that the big vaccination campaign will really get going one day, "it has to," he says. Even today, Horst L. has calculated, more than 500,000 vaccinations would have to be administered every day throughout Germany for the Chancellor's campaign promise to vaccinate 70 percent of the population by the time of the general election to come true. "Recently, however, not even 70,000 a day were vaccinated." So it must be accelerated, he said, and then his chances of restepiks out of line would also fall. "I remain an optimist, but I'm also a realist," L. says, "and as one, I know that the alternative to waiting here in the IZ makes me look even worse."

Even in his age group, after all, he says, the famously organizational Germans barely managed to vaccinate around eight percent of the very elderly in the first nearly eight weeks. "If I calculate that there are naturally more 70-year-olds, then you won't be through with them before the end of June."

L. hopes to be through with his vaccination by then. "I have high hopes for Astrazeneca, because nobody wants the vaccine." All the greater would be the leftovers that remain in the next few days. "That's bound to drop some for me soon," he says, waving to a vaccination nurse and walking slowly back to his improvised camp at the edge of the tribe's large vaccination hall.