Read it at your own pace.

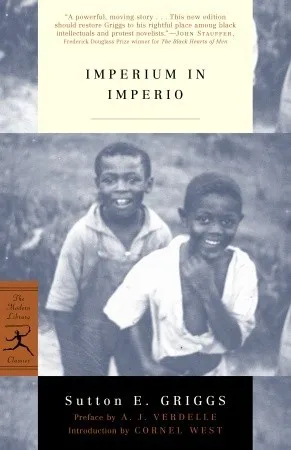

CHAPTER VI.

A YOUNG REBEL.

In the city of Nashville, Tennessee, there is a far famed institution of learning called Stowe University, in honor of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin."

This institution was one of the many scores of its kind, established in the South by Northern philanthropy, for the higher education of the Negro.

Though called a university, it was scarcely more than a normal school with a college department attached.

It was situated just on the outskirts of the city, on a beautiful ten-acre plot of ground.

The buildings were five in number, consisting of a dormitory for young men, two for young ladies, a building for recitations, and another, called the teachers' mansion; for the

teachers resided there.

These buildings were very handsome, and were so arranged upon the level campus as to present a very attractive sight.

With the money which had been so generously given him by Mr. King, Belton entered this school.

That was a proud day in his life when he stepped out of the carriage and opened the University gate, feeling that he, a Negro, was privileged to enter college.

Julius Caesar, on entering Rome in triumph, with the world securely chained to his chariot wheels; Napoleon, bowing to receive the diadem of the Caesars' won by the most notable victories ever known to earth; General Grant, on his triumphal tour around the globe, when kings and queens were eager rivals to secure from this man of humble birth the sweeter smile; none of these were more full of pleasurable emotion than this poor Negro lad, who now with elastic step and beating heart marched with head erect beneath the arch of the doorway leading into Stowe University.

Belton arrived on the Saturday preceding the Monday on which school

would open for that session.

He found about three hundred and sixty students there from all parts of the South, the young women outnumbering the young men in about the proportion of two to one.

On the Sunday night following his arrival the students all assembled in the general assembly room of the recitation building, which room, in the absence of a chapel, was used as the place for religious worship.

The president of the school, a venerable white minister from the North, had charge of the service that evening.

He did not on this occasion preach a sermon, but devoted the hour to discoursing upon the philanthropic work done by the white people of the North for the freedmen of the South.

A map of the United States was hanging on the wall, facing the assembled school.

On this map there were black dots indicating all places where a school of learning had been planted for the colored people by their white friends of the North.

Belton sat closely scrutinizing the map.

His eyes swept from one end to the other.

Persons were allowed to ask any questions desired, and Belton was very

inquisitive.

When the hour of the lecture was over he was deeply impressed with three thoughts:

First, his heart went out in love to those who had given so freely of their means and to those who had dedicated their lives to the work of uplifting his people.

Secondly, he saw an immense army of young men and women being trained in the very best manner in every section of the South, to go forth to grapple with the great problems before them.

He felt proud of being a member of so promising an army, and felt that they were to determine the future of the race.

In fact, this thought was reiterated time and again by the president.

Thirdly, Belton was impressed that it was the duty of those receiving such great blessings to accomplish achievements worthy of the care bestowed.

He felt that the eyes of the North and of the civilized world were upon them to see the fruits of the great labor and money spent upon them.

Before he retired to rest that night, he besought God to enable him and his people, as a mark of appreciation of what had been done for the race, to rise to the full measure of just expectation and prove worthy of all the care bestowed.

He went through school, therefore, as though the eyes of the world were looking at the race enquiringly; the eyes of the North expectantly; and the eyes of God lovingly,--three

grand incentives to his soul.

When these schools were first projected, the White South that then was, fought them with every weapon at its command.

Ridicule, villification, ostracism, violence, arson, murder were all employed to hinder the progress of the work.

Outsiders looked on and thought it strange that they should do this.

But, just as a snake, though a venomous animal, by instinct knows its enemy and fights for its life with desperation, just so the Old South instinctively foresaw danger to its social fabric as then constituted, and therefore despise and fought the agencies that were training and inspiring the future leaders of the Negro race in such a manner as to render a conflict inevitable and of doubtful termination.

The errors in the South, anxious for eternal life, rightfully feared these schools more than they would have feared factories making powder, moulding balls and fashioning cannons.

But the New South, the South that, in the providence of God, is yet to be, could not have been formed in the womb of time had it not been for these schools.

And so the receding murmurs of the scowling South that was, are lost in the gladsome shouts of the South which, please God, is yet to be.

But lest we linger too long, let us enter school here with Belton.

On the Monday following the Sunday night previously indicated, Belton walked into the general assembly room to take his seat with the other three hundred and sixty pupils.

It was the custom for the school to thus assemble for devotional exercises.

The teachers sat in a row across the platform, facing the pupils.

The president sat immediately in front of the desk, in the center of the platform, and the teachers sat on either side of him.

To Belton's surprise, he saw a colored man sitting on the right side of and next to the president.

He was sitting there calmly, self-possessed, exactly like the rest.

He crossed his legs and stroked his beard in a most matter of fact way.

Belton stared at this colored man, with his lips apart and his body bent forward.

He let his eyes scan the faces of all the white teachers, male and female, but would end up with a stare at the colored man sitting there.

Finally, he hunched his seat-mate with his elbow and asked what man that was.

He was told that it was the colored teacher of the faculty.

Belton knew that there was a colored teacher in the school but he had no idea that he would be thus honored with a seat with the rest of the teachers.

A broad, happy smile spread over his face, and his eyes danced with delight.

He had, in his boyish heart, dreamed of the equality of the races and sighed and hoped for it; but here, he beheld it in reality.

Though he, as a rule, shut his eyes when prayer was being offered, he kept them open that morning, and peeped through his fingers at that thrilling sight,--a colored man on equal terms with the white college professors.

Just before the classes were dismissed to their respective class rooms, the teachers came together in a group to discuss some matter, in an informal way.

The colored teacher was in the center of the group and discussed the matter as freely as any; and he was listened to with every mark of respect.

Belton kept a keen watch on the conference and began rubbing his hands and chuckling to himself with delight at seeing the colored teacher participating on equal terms with the other teachers.

The colored teacher's views seemed about to prevail, and as one after another the teachers seemed to fall in line with him Belton could not contain himself longer, but clapped his hands and gave a loud, joyful, "Ha! ha!"

The eyes of the whole school were on him in an instant, and the faculty turned around to discover the source and cause of the disorder.

But Belton had come to himself as soon as he made the noise, and in a twinkling was as quiet and solemn looking as a mouse.

The faculty resumed its conference and the students passed the query around as to what was the matter with the "newcomer."

A number tapped their heads significantly, saying:

"Wrong here."

How far wrong were they!

They should have put their hands over their hearts and said:

"The fire of patriotism here;" for Belton had here on a small scale, the gratification of the deepest passion of his soul, viz., Equality of the races.

And what pleased him as much as anything else was the dignified, matter of fact way in which the teacher bore his honors.

Belton afterwards discovered that this colored man was vice-president of the faculty.

On a morning, later in the session, the president announced that the faculty would hold its regular weekly meeting that evening, but that he would have to be in the city to attend to other masters.

Belton's heart bounded at the announcement.

Knowing that the colored teacher was vice-president of the faculty, he saw that he would preside.

Belton determined to see that meeting of the faculty if it cost him no end of trouble.

He could not afford, under any circumstances, to fail to see that colored man preside over those white men and women.

That night, about 8:30 o'clock, when the faculty meeting had progressed about half way, Belton made a rope of his bed clothes and let himself down to the ground from the window of his room on the second floor of the building.

About twenty yards distant was the "mansion," in one room of which the teachers held their faculty meetings.

The room in which the meeting was held was on the side of the "mansion" furthest from the dormitory from which Belton had just come.

The "mansion" dog was Belton's friend, and a soft whistle quieted his bark.

Belton stole around to the side of the house, where the meeting was being held.

The weather was mild and the window was hoisted.

Belton fell on his knees and crawled to the window, and pulling it up cautiously peeped in.

He saw the colored teacher in the chair in the center of the room and others sitting about here and there.

He gazed with rapture on the sight.

He watched, unmolested, for a long while.

One of the lady teachers was tearing up a piece of paper and arose to come to the window to throw it out.

Belton was listening, just at that time, to what the colored teacher was saying, and did not see the lady coming in his direction.

Nor did the lady see the form of a man until she was near at hand.

At the sight she threw up her hands and screamed loudly from fright.

Belton turned and fled precipitately.

The chicken-coop door had been accidentally left open and Belton, unthinkingly, jumped into the chicken house.

The chickens set up a lively cackle, much to his chagrin. He grasped an old rooster to stop him, but missing the rooster's throat, the rooster gave the alarm all the more vociferously.

Teachers had now crowded to the window and were peering out.

Some of the men started to the door to come out.

Belton saw this movement and decided that the best way for him to do was to play chicken thief and run.

Grasping a hen with his other hand, he darted out of the chicken house and fled from the college ground, the chickens squalling all the while.

He leapt the college fence at a bound and wrung off the heads of the chickens to stop the noise.

The teachers decided that they had been visited by a Negro, hunting for chickens; laughed heartily at their fright and resumed deliberations.

Thus again a patriot was mistaken for a chicken thief; and in the South to-day a race that dreams of freedom, equality, and empire, far more than is imagined, is put down as a race of chicken thieves.

As in Belton's case, this conception diverts attention from places where startling things would otherwise be discovered.

In due time Belton crept back to the dormitory, and by a signal agreed upon, roused his room-mate, who let down the rope, by means of which he ascended; and when seated gave his room-mate an account of his adventure.

Sometime later on, Belton in company with another student was sent over to a sister University in Nashville to carry a note for the president.

This University also had a colored teacher who was one point in advance of Belton's.

This teacher ate at the same table with the white teachers, while Belton's teacher ate with the students.

Belton passed by the dining room of the teachers of this sister University and saw the colored teacher enjoying a meal with the white teachers.

He could not enjoy the sight as much as he would have liked, from thinking about the treatment his teacher was receiving.

He had not, prior to this, thought of that discrimination, but now it burned him.

He returned to his school and before many days had passed he had called together all the male students.

He informed them that they ought to perfect a secret organization and have a password.

They all agreed to secrecy and Belton gave this as the pass word:

"Equality or Death."

He then told them that it was his ambition and purpose to coerce the white teachers into allowing the colored teacher to eat with them.

They all very readily agreed; for the matter of his eating had been thoroughly canvassed for a number of sessions, but it seemed as though no one dared to suggest a combination.

During slavery all combinations of slaves were sedulously guarded against, and a fear of combinations seems to have been injected into the Negro's very blood.

The very boldness of Belton's idea swept the students away from the lethargic harbor in which they had been anchored, and they were eager for action.

Belton was instructed to prepare the complaint, which they all agreed to sign.

They decided that it was to be presented to the president just before devotional exercises and an answer was to be demanded forthwith.

One of the young men had a sister among the young lady students, and, through her Belton's rebellion was organized among the girls and their signatures secured.

The eventful morning came.

The teachers glanced over the assembled students, and were surprised to see them dressed in their best clothes as though it was the Sabbath.

There was a quiet satisfied look on their faces that the teachers did not understand.

The president arrived a little late and found an official envelope on his desk.

He hurriedly broke the seal and began to read.

His color came and went.

The teachers looked at him wonderingly.

The president laid the document aside and began the devotional exercises.

He was nervous throughout, and made several blunders.

He held his hymn book upside down while they were singing, much to the amusement of the school.

It took him some time to find the passage of scripture which he desired to read, and after reading forgot for some seconds to call on some one to pray.

When the exercises were through he arose and took the document nervously in hand.

He said; "I have in my hands a paper from the students of this institution concerning a matter with which they have nothing to do.

This is my answer.

The classes will please retire."

Here he gave three strokes to the gong, the signal for dispersion.

But not a student moved.

The president was amazed.

He could not believe his own eyes.

He rang the gong a second time and yet no one moved.

He then in nervous tones repeated his former assertions and then pulled the gong nervously many times in succession.

All remained still.

At a signal from Belton, all the students lifted their right hands, each bearing a small white board on which was printed in clear type:

"Equality or Death."

The president fell back, aghast, and the white teachers were all struck dumb with fear.

They had not dreamed that a combination of their pupils was possible, and they knew not what it foreboded.

A number grasped the paper that was giving so much trouble and read it.

They all then held a hurried consultation and assured the students that the matter should receive due attention.

The president then rang the gong again but the students yet remained.

Belton then arose and stated that it was the determination of the students to not move an inch unless the matter was adjusted then and there.

And that faculty of white teachers beat a hasty retreat and held up the white flag!

They agreed that the colored teacher should eat with them.

The students broke forth into cheering, and flaunted a black flag on which was painted in white letters;

"Victory."

They rose and marched out of doors two by two, singing "John Brown's Body lies mouldering in the grave, and we go marching on."

The confused and bewildered teachers remained behind, busy with their thoughts.

They felt like hens who had lost their broods.

The cringing, fawning, sniffling, cowardly Negro which slavery left, had disappeared, and a new Negro, self-respecting, fearless, and determined in the assertion of his rights was at hand.

Ye who chronicle history and mark epochs in the career of races and nations must put here a towering, gigantic, century stone, as marking the passing of one and the ushering in of another great era in the history of the colored people of the United States.

Rebellions, for one cause or another, broke out in almost every one of these schools presided over by white faculties, and as a rule, the Negro students triumphed.

These men who engineered and participated in these rebellions were the future leaders of their race.

In these rebellions, they learned the power of combinations, and that white men could be made to capitulate to colored men under certain circumstances.

In these schools, probably one hundred thousand students had these thoughts instilled in them.

These one hundred thousand went to their respective homes and told of their prowess to their playmates who could not follow them to the college walls.

In the light of these facts the great events yet to be recorded are fully accounted for.

Remember that this was Belton's first taste of rebellion against the whites for the securing of rights denied simply because of color.

In after life he is the moving, controlling, guiding spirit in one on a far larger scale; it need not come as a surprise.

His teachers and school-mates predicted this of him.

Now it starts getting good,....